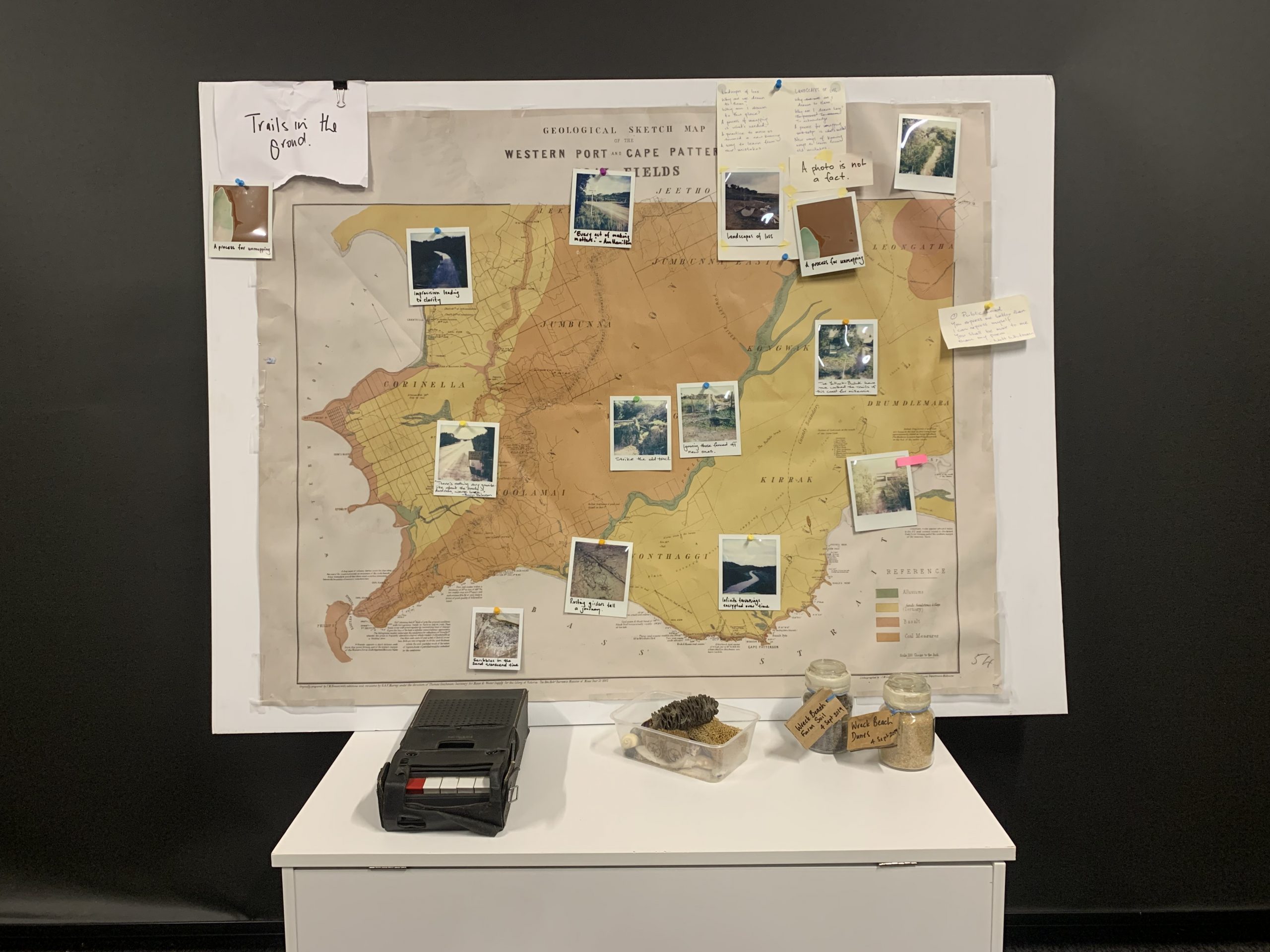

Trails in the Ground (installation & essay)

Articulating the idiosyncrasies and agency of the entanglement of tracks that are encrypted on every aspect of the Bunurong Coast, the final iteration of ‘A Trail in the Ground’ explores how those marks—and the past happenings and traversings they embody—influence how I perceive and interact with every other place I have inhabited, now and into the future.

Responding to the tracks and trails that crisscross the landscape, it also engages with the complexities, silences and violence of inter-generational conflict that can be read. It is those sometimes thorny, often uncomfortable, and occasionally joyous layered encrypted meanings that the work attempts to disentangle and survey. This final iteration also attempts to articulate the ancient and contemporary meanings and knowledges embodied in these byways – it unpicks the enigmatic and subjective truths that can be deciphered through research, careful observation, and speculation.

XXXX

A Trail in the Ground: Speculating on the intimate histories of place

[Audio: The sound of walking a clifftop trail on the Bunurong Coast. Recorded 23 September 2022.]

This yarn is framed around the trails, those both haphazard and deliberate, that inhabit a particular Australian locale. It is a story about pathfinding, how we read the signs in the ground, in the skies and in the waterways. How we speculate on the ever-changing meanings and the different histories that can be ascribed to those marks. This exploration could be set in nearly any Australian region, but the locative case study I use is deliberately specific and intimate. The focus of our journey is an unruly coastal region in Victoria’s south-east, a place often known as the Bunurong Coast.

The Bunurong Coast is the place of my birth, where I grew up, and where I now live. It is also a place that I lived away from for more than twenty years. However, during that time spent elsewhere, its scrubby heaths, its secluded dunes, and the meandering trails that run through them, stayed with me. My thoughts would constantly return there – it has always been the place of my daydreaming and reflection.

The deep affinity I possess for this place is informed by intimate and inter-generational connections, by diverse and parochial histories, by literature, as well as by countless days and nights spent exploring the nooks, burrows and hollows of its dunes, its scrub and its trails. The idiosyncrasies and authority of the entanglement of tracks encrypted into every aspect of this place both informs and taints my view and understandings. Those marks and whispers of past happenings and traversings influence how I perceive and interact with every other place I have, and will, inhabit.

My affinity for this place is not all affirmative. My inhabitation of Bunurong / Boonwurrung Country results from inter-generational theft and dispossession. This was stolen land and its custodianship remains contested land.[1] The complexities, silences and violence of this inter-generational conflict are embedded into the tracks and trails that crisscross this place. It is those sometimes thorny, often uncomfortable and occasionally joyous histories we’re attempting to disentangle and survey.

Ancient meaning and knowledges are encrypted into these byways – enigmatic and subjective truths that can be deciphered through research, careful observation and speculation. Aboriginal songs and dreaming are ever present, as Boonwurrung elder Aunty Fay Muir writes, “Our way is old, older than red earth, older than flickering stars.”[2] Much of this ancient knowledge is known only to initiated mob but a considerable body of language and cultural practice has also been generously shared. We’ll lean on that amazing work on this journey.

Today we’ll take an informed and reflective ramble through a particular section of the Bunurong Coast. We’ll use prose, Polaroid photography, audio, and multimedia recordings to interrogate and amalgamate the imprints, titbits, echoes associated with this place’s tracks and trails, and their histories. It is those tools that scaffold the structure of this story. Our walk will see us visit four specific locations, each containing a trail, a track, a path, or a road that provides a prompt for reflection, speculation and meaning making.

This physical/creative ramble is one undertaken as a means to unpick the everyday personal, historical and literary forces that shape and complicate this post-colonial Australian region. Ultimately, this story is my personal creative response to a specific regional landscape, and the personal associations I have to it. It traverses a specific route to explore how one might do place-based history creatively and respectfully. Crucially, it also demonstrates why it is important to do those things.

OUR AREA OF CONCERN

The place we’re visiting is decidedly specific, located as it is on the back roads of an unruly stripe of Victoria’s southeastern coastline. This tract of land, water and air stretches from.

This is a firmly regional and parochial place, sandwiched between Harmers Haven, Cape Paterson and Wonthaggi. The isolated remoteness of this place was certainly more acute during the European invasion of Victoria. The ‘Westernport region’ was certainly beyond the periphery of what was then considered ‘civilised society’. However, as a frontier for the colonial project, it was also a place that was attracting a great deal of attention for how it could be possessed and exploited for profit. There was coal to be dug, lands to be cleared and grazed, timber and lime to be taken and sold.[3]

A compelling nexus of historic occurrences – an array of happenings spanning the parochial, eccentric through to significant – certainly took place here. These histories have resulted in a diverse collection of archival and literary material – encompassing bulky official tomes but also a mishmash of parochial and highly personal material. These fragments – sourced from archival and literary collections, as well as from memories, personal reflection, and in the landscape itself – provide intimate and deeply moving insights. But the act of cajoling this disparate and dishevelled collection of records and experience into an artefact that communicates some semblance of cohesive meaning is easier said than done. What’s needed is aesthetic forms deliberately created to “contain, focus and direct the forces of the past” but ones intentionally focused so “they can be comprehended and channeled in such a way that meanings and feelings implicit to the past might get effectively communicated to the people of the present”.[4]

LOCATION 1 – Wreck Beach Farm Gate, Cape Paterson

[Audio: 'A Trail In The Ground' read by Rees Quilford.]

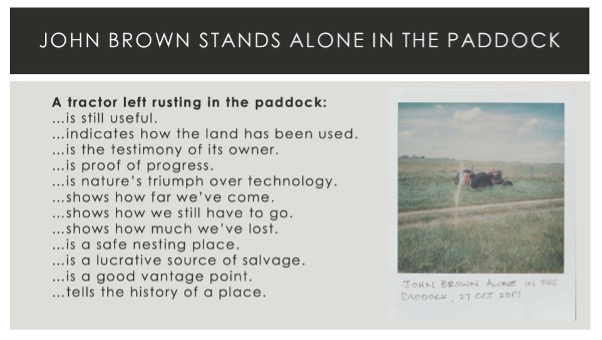

We start today’s talk at the front gate of Wreck Beach Farm, a property that was purchased by my father’s parents in the early 1950s. After they passed, my parents assumed responsibility for its care, they farmed it for more than thirty years.

It’s a beautiful farm, one that has benefited from years of rewilding, but the ground here is riddled with rutted trails worn by the repeated journeys of tractor tires, boots and livestock.

Many of those marks are evidence of countless journeys made on a temperamental 1962 Ford tractor that my father coaxed to life each morning. They meander away in all directions, passing battered hardwood posts, wildlife trails, rusting star pickets, and rotting tangles of sheep wire. Tiny monuments to the toil, triumphs, and misjudgments of some of those who have passed before.

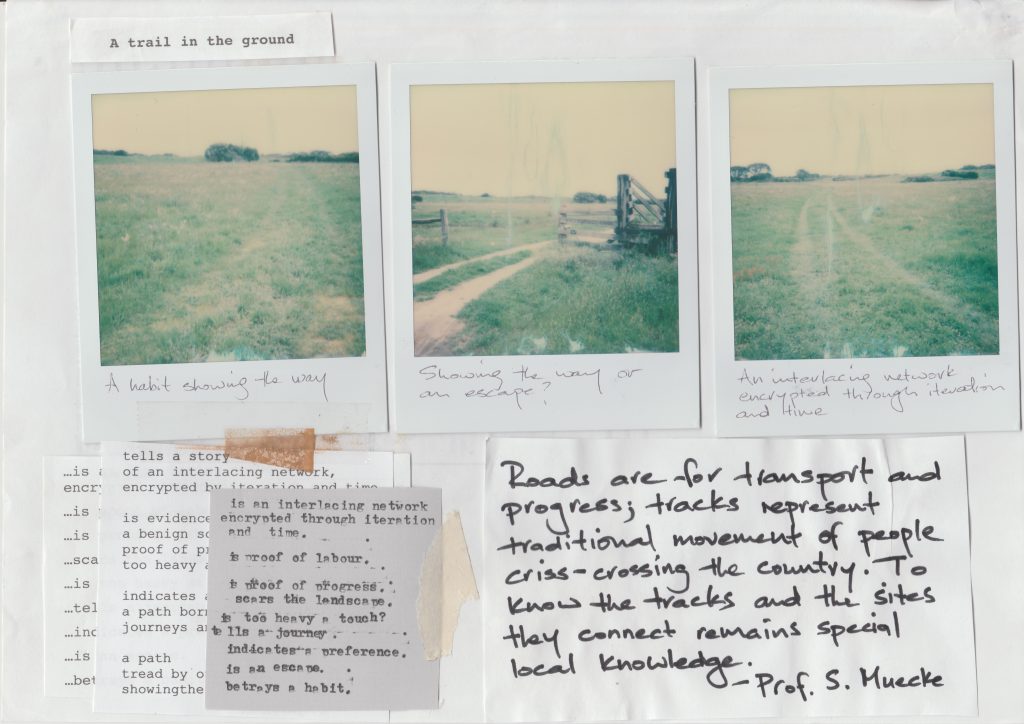

There are multiple, and often contradictory, meanings that can be read into these seemingly mundane marks. They can be interpreted as an interlacing network encrypted through iteration and time. They are proof of labour. Proof of progress, some might say. They could be seen as scars in the landscape, too heavy at touch. These trails in the ground tell of journies and indicate preferences. They betray habits and escape routes.

The furrows inscribed by my family’s agricultural practices are evidence of an intergenerational connection to place but they are also evidence of conflict with the land itself.

Walking the rises and heaths of Wreck Beach Farm, or nearly any other farm in regional Australia for that matter, you are quickly confronted by a conflict between industrialised agricultural practice and the limits of the natural world.

In many instances, this conflict can be observed via damage and disfigurement inflicted upon of the landscape. Slang heaps covered in thistles and ragweed, collapsed mine shafts, drained waterholes, and erosion lines. But in many cases, the marks of agriculture can be seen not so much as blemishes, rather they are symbols and representations of repeated and returning journeys.

In some cases, these marks are enhancements, encouraging reminders that the land, the waters and the skies were meant to be traversed.

LOCATION 2 – Old Boiler Road, Harmer's Haven

We’ll leave the Wreck Beach farm gate now and head southwest towards the ocean. It is a route that takes us toward the Yallock-Bulluk Marine and Coastal Park.

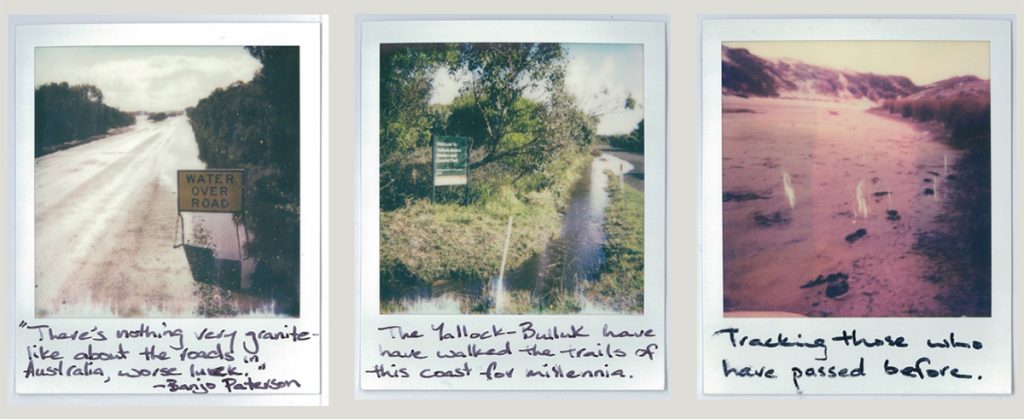

As we amble along the potted redstone gravel of Old Boiler Road it seems sensible to check in with some writers far more well-credentialed than I for their reflections on traversing Australian’s backroads:

“There is nothing very granite-like about the roads in Australia, worse luck.

Ruts and loose metal, sidelings and sand drifts, washed out creeks and heart-breaking hills.”

- Andrew Barton Paterson, ‘Overland to Melbourne on an Automobile — The History of the Haste-Wagons No 1’

Banjo Paterson wrote of Australia’s early Federation roads. This hankering for granite-like certainty seems a common refrain in the canon of Australian colonial poetry. Permanency and fixed meanings are not something I observe nor desire here on the Bunurong Coast so it seems apt that the unkept state articulated by Paterson persisted on these coastal roads well into the 1970s. As long-time Wonthaggi resident, Frank Coldabella recounts:

“The unmade coast road was a narrow track – longer, windier and very rough, with deep rabbit and wombat holes.”

- Frank Coldabella 'The hut people'

Ramshackle huts dotted the bays of this coastline from the early 1900s into the 1970s. Those shacks provided weekend and, in some cases, permanent, retreats for the region’s coalminers and families. The tracks used to get from the town to those coastal huts – and the people that traversed them – were inclined toward walking. As Frank (again) reminisces:

“Even after cars became common, some of the old people preferred to walk to the beach. The track [sic] crossed paddocks, wound through woodlands and skirted wetlands. This slow pilgrimage was part of the ritual, allowing the mind to leave behind the town’s clamour. The thin line of blue sea coming into view was a moment of pure joy.”

- Frank Coldabella 'The hut people'

From where we’re located, we only have to wander half a mile down the road to reach the network of coastal dunes that marks the edge of the Yallock-Bulluk Marine and Coastal Park.

The first storytellers of this place have walked the tracks and beaches of this coastline for millennia. Middens teeming with bleached shell fragments from generation upon generation of Bunurong/Boonwurrung king-tide feasts can be seen throughout the dunes that lay ahead of us.

Conceptualising Australia’s roads as spatial narratives encompassing multi-layered historical and contemporary inscriptions, Australian historian Kiera Lindsey suggests that roads avail themselves to multiple acts of traversing.[5]

By thinking of them as spatial and temporal narratives, we can trace the process through which previous trajectories have inscribed meaning onto a road, a track or a trails. Not only that, as travelers and observers, we can also be writers of these spatial narratives.

In this way, the tracks and trails of this place can be read as aftereffects of repeated journeys, remembrances of happenings and travel. We heard Frank Coldabella's recollections on walking the bog tracks, so following Lindsey's cue to consider infinite layering of journeys taken, let us now consider longtime Wonthaggi resident's Jim Longstaff reminiscing on navigating the sandy rises and swampy hallows of the walking trail that afforded access to Wreck Beach.

[Audio: Jim Longstaff (interviewed by Joe Chambers) reflecting on navigating the sandy rises and swampy hallows of the track to the Wreck Beach as a boy in the 1920s. Wonthaggi & District Historical Society, Oral History Recording OH-0077, recorded 12th August, 1987]

Across the regions of Australia, the process of white settlement saw the traditional walking tracks made and used by Indigenous peoples appropriated by explorers and then the settlers and pastoralists that followed. Paths became tracks, then roads and highways. This is certainly the experience here on the Bunurong Coast. The early geological surveys and maps of the area often chart the well-worn walking routes of the Bunurong/Boonwurrung, denoting them as ‘Black tracks’ and ‘native trails’.[6] Those routes were often accompanied by annotations noting their suitability for the roads, skiplines and tram tracks that would be used to log the blackwood forests, mine the coal steams and open the land up for farming. Unsurprisingly, many modern-day roads follow those same routes.

On the practice and ethics of visiting country, Stephen Muecke discusses the paradoxes of visiting Indigenous lands as a non-Indigenous Australian. Researchers, he suggests, are inevitably in the business of stories, but as visitors in Aboriginal Country, visiting protocols apply. A key approach to reconcile this conundrum involves maintaining an ‘aesthetic attitude of respectful visitation’. One involving paying heed to visiting protocols and maintaining impeccable behaviour. This is an approach we’ll attempt to embrace on this amble. We’ll also reflect on the thoughts Muecke offers on the act of traversing roads as opposed to travelling trails:

“Roads are for transport and progress; tracks represent traditional movement of people criss-crossing the country. To know the tracks and the sites they connect remains special local knowledge.”[7]

The Aboriginal knowledge of this place is not for me to know or tell but I do possess an intimate connection and deeply personal local knowledge of many of the tracks and sites that inhabit this place. In that awareness and knowledge, I try to remain attuned to the violence of settlement and to acts of colonial appropriation and erasure. At the same time, I try to remain open to the innate mystery, splendour and imaginative inspiration they inspire.

On today’s journey, we’re tracing and retracing the process through which the modern-day roads of the Bunurong Coast ‘came into being’. This presents opportunities to focus on – and perhaps re-centre – that which has been pushed to the margins and erased. The traversings that have been encrypted into these routes over millennia – by the Bunurong/Boonwurrung, by more recent visitors, and by animals, plants and the elements – and the importance of those diverse histories – is brought into greater focus.

LOCATION 3 – Wreck Beach Carpark

Let’s now wander a couple of hundred metres down the road to the carpark that services the stunning crescent bay lying in the heart of the place that we’re yakking on about. Wreck Beach is the name by which this place currently known. This place has borne witness to three shipwrecks and a beached whale whose jawbones now adorn the façade of a nearby pub. A weathered bluestone cairn on the verge of the scrub was placed to commemorate the explorer William Howell’s ‘discovery’ of black coal in 1826. My grandfather was amongst those who advocated for its placement in the 1970s.

The brass plaque the group had cast cited his name incorrectly (he was named as Thomas Howell, not William). The replacement plaque was jimmied years ago and the scrub is slowly reclaiming that hilariously parochial monument to colonial endeavour.

The brass plaque the group had cast cited his name incorrectly (he was named as Thomas Howell, not William). The replacement plaque was jimmied years ago and the scrub is slowly reclaiming that hilariously parochial monument to colonial endeavour.

Let us now walk through the scrub down to the brackish creek that seperates us from the ocean. Rude huts built in the early-1840s by the coal exploration team that worked those seams once stood on this creek. Those huts and the nearby dunes were the site of an 1841 confrontation between a group of Tasmanian Aboriginals dubbed the ‘Van Dieman's Land Blacks’[8] – Tunnerminnerwait (Parperloihener clansman), Planobeena (a Tasmanian Aboriginal woman from Port Dalrymple), Maulboyheenner (a bungunna (leader) from the north-eastern Tasmanian region known to his people as Nalebunner), Truganini (a Tasmanian Aboriginal woman of Bruney Island) and Pyterruner (a Tasmanian Aboriginal woman) – and a European whaling party which left two of the whalers, William Cook and Yankee, shot dead. The Aboriginal group spent the following weeks and months between fight and flight, raiding homesteads across the Westernport district while evading parties of mounted Border Police and squatter posses. Their ultimate capture led to the first executions in the colony of Victoria, the hanging in January 1842 of Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner.[9]

Because of these occurrences, Wreck Beach is a place where one can track through a rich collection of archives and literary sources to speculate upon occurrences that have passed before. But there is also so much that can be read into the landscape itself, in the marks on the trees, in the impossibly big sky, in the natural soaks and the brackish creek. The tracks and trails that inhabit the skies, the seas and the sandy soils offer as rich – if not richer – sources for imagination and creative speculation.

LOCATION 4 – On the dune line

We see this in the wildlife trials that breach the barbed wire fences and crisscross the walking trail that we’re following to get down to the beach. The course they chart is guided by primal instinct, cunning and convenience. They operate as routes for entry and escape. They track between hunting grounds, water sources and the safety of dens, warrens and nests. These trails embrace instinct and intuition. They provide safety and convenience of access. They follow the natural contours of the land.

Given we’re now making our way from along a winding scrubby trail that leads from the carpark down to the beach, it seems apt to borrow[10] from the sentiments of Adam Lindsey Gordon’s ‘vigorous tale in verse’.[11] From the Wreck. The 1870 poem traces an epic 18-mile steeplechase through the wild coastal trails made by two stockriders ‘riding for their souls’ to summon relief for the survivors of a passenger steamship that lay wrecked on a submerged reef.

The sentiment that most resonates is the intuitive local knowledge of the riders. This deeply intimate familiarity allows them to traverse ‘the near cuts’, sure of the crossing-places, they strike the old track while ignoring those fenced-off new ones:[12]

In the low branches heavily laden with dew,

In the long grasses spoiling with deadwood that day,

Where the blackwood, the box, and the bastard oak grew,

Between the tall gum-trees we gallop’d away—

We crashed through a brush fence, we splash’d through a swamp—

We steered for the north near ‘The Eaglehawk’s Nest’—

We bore to the left, just beyond ‘The Red Camp’,

And round the black tea-tree belt wheel’d to the west—We cross’d a low range sickly scented with musk

From wattle-tree blossom—we skirted a marsh—

Then the dawn faintly dappled with orange the dusk,

And peal’d overhead the jay’s laughter note harsh,

And shot the first sunstreak behind us, and soon

The dim dewy uplands were dreamy with light;

And full on our left flash’d ‘The Reedy Lagoon,’

And sharply ‘The Sugarloaf’ rear’d on our right.

Meandering trails that start and stop in a heartbeat.- Adam Lindsey Gordon 'From the Wreck' in Bush Ballads (1870).

These vivid passages speak of the familiarity and skill – both learned and innate – required to traverse winding trails, overflowing river fords and haphazard tracks that inhabit Australia’s coastline.

Navigating the unruly and beautiful complexity of these unruly dunes and plains requires special local knowledge, something akin to what Bundjalung poet Evelyn Araluen alludes to when she writes, “Every life I have knows this reserve and the liminal scrub it spills through”.[13]

These are tracks and trails that casually disregard the rigid protocols of civilized society. They are oblivious to the colonial inclination toward appropriation and sub-division. Knowing their ways and idiosyncrasies is a gift.

DOWN ON THE BEACH

We’ve now reached the threshold of land and sea, a brackish creek cuts through the dunes and meets the sea. The long arching bay is flanked at either end by rock platforms and rolling swells. Standing here prompts consideration of the migratory paths that track through the skies and the waters of this place. From May through to October, the waters of this coast form part of the ocean highway traversed by Humpback Whales, Southern Right Whales, and Orcas as they migrate from Antarctica to the warmer waters up north for calving.

These same waters offer a lifeblood byway for the epic migration Victorian freshwater eels make at both the start and end points of their existences. The sole spawning site of these eels is located in the Coral Sea to the southeast of New Guinea. Beginning their lives at this site, as tiny transparent larvae, they are then carried southwards by the ocean currents that parallel Australia’s eastern coast. Amazingly, each eel navigates a nearly 3000km journey back to the exact ancestral estuaries of their forebearers. Once home, they spend the next dozen years feeding, maturing, and nurturing the lagoons, estuaries, rivers and water soaks of their intergenerational home.[14]

At maturity, eels transform in preparation for the spawning migration they will make. After a period of voracious feeding, and significant growth, they depart these waters and return to the place of their birth. Quickly seeking the ocean’s depths, they make their way north against the current in total darkness. They expend their life reserves to reach the Coral Sea, where they spawn and die so that the cycle can recommence.

Wailwan/Kamilaroi architect, scholar, and educator Jefa Greenway highlights the power of the metaphor of the eel’s journey, “Not only do the eels transmogrify when they move from salt water to fresh water and back again, their migration patterns also connect in a global sense. Water stories and water bodies connect through time and Country. This is a story which can resonate with anybody. The eel migration enables us to have a sense of pride, to celebrate connection to the oldest continuing culture in the world. It provides an opportunity to celebrate Indigenous culture and to showcase Indigenous culture as part of our everyday experience.”[15]

The ancient inter-generational migration of the eel – and the similarly epic airborne migrations made by the Shearwater and Muttonbirds of this coastline – offer a humbling glimpse into the elemental magnetism of this place. The instinctive and intuitive pathways they find also highlight the ridiculous folly of the colonial complusion to impose systematic order, borders and control over the byways and traversings of the Bunurong Coast.

It’s not just the epic migratory journeys and the grand historical happenings that have occurred here at Wreck Beach which are important. The mundane and the ordinary experiences that have taken place here are just special. Wreck Beach has always been a popular weekend retreat for the Wonthaggi residents. Day trips have been enjoyed. Long meandering walks have been made. Sandy picnic lunches have been eaten, tens of thousands of hours have been wiled away rockpooling and sunbathing. Hands have been held, tears shed, and kisses have been exchanged.

This was especially true in the years following the establishment of the town of Wonthaggi. In the first decades of the 1900s entire families would walk to the beach and back each and every weekend through the summer months. Local resident Ricky Pryor, who grew up as one of eight children in Wonthaggi household, describes the regular pilgrimage with vivid detail.

Ricky Prior (interviewed by Joe Chambers) discusses the ritual of families walking from Wonthaggi to Wreck Beach every summer weekend through the 1910s and 1920s. [Wonthaggi & District Historical Society, Oral History Recording OH-0051, recorded 18th June 1982] [16]

Joe & Lynn Chambers also describe the appeal of trekking to this beach with great eloquence, ‘“Let’s go to the Wreck” was a hot weather call’ they write ‘“The Wreck” meant long, haphazard unplanned hours of climbing, sliding, rolling, swimming, diving, fishing, wandering, kite-flying (there was no shortage of wind), lazing and talking well away from the adult constraints and concerns of town. “The Wreck” was freedom.’[17]

It was also a place of great abundance. Wreck beach has also long been a popular spot for fishing and cray fishing. Longtime local resident Arthur Featherstone told a gobsmacking yarn about catching 18 crayfish in the 1920s, using just a piece of cord and a net.

Arthur Featherstone (interviewed by Joe Chambers) discusses crayfishing at Wreck Beach in the 1920s. [Wonthaggi & District Historical Society, Oral History Recording OH-0054, recorded 16th September 1982]

THE END OF OUR RAMBLE

Thank you for joining me on my journey today. I hope our shared experience helps remind you that while it’s easy to dismiss the significance of the diverse network of trails and tracks that occupy the Bunurong Coast but doing so undersells the place. This is not what the cultural geographer Doreen Massey would call a ‘retreat place’, a walled off, singular and representational location somehow originally regionalised, as always-already divided up.

That is not what we see perceived in the tracks that riddle and enrich the ground and waters of the Bunurong Coast. Instead, what we can see is an intricate ecosystem overflowing with complex sounds, smells, and emotions. We see vast and complex webs of deeply personal relationships between humans, animals, the elements and the place itself.

When you take the time to properly, and respectfully, ponder the embodied meanings that can be read into the marks that surround us you glimpse fluidly and mutability. Never finished, never closed, always in the process of being made, these tracks are speculative and ever-changing events. They are performances that can be reimagined, interrogated and retold in infinite ways.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

[1] The Bunurong Coast remains contested land on multiple fronts. Like all of Australia, this is true in relation to the lack of progress on reconciliation, truth-telling and treaty for Australia’s Indigenous and First Nations peoples. However, the formal recognition as the Bunurong’s traditional owner group also remains a contested matter. The Bunurong Land Council achieved recognition as the Registered Aboriginal Party (RAP) under the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Act but this ruling is being contested by the BoonWurrung Land and Sea Council. I know I approach this country from a position of privilege and complacency. How I – and others – go about acknowledging the violence and wantonly unlawful theft of these lands is constantly front of mind. My conduct and the actions I undertake to reconcile continuing to live on, and connect with, Bunurong land are also crucially important to me.

[2] Aunty Fay Muir & Lisa Kennedy (2020) ‘Respect’, Magabala Books.

[3] The shameful collective legacies of these activities cannot be overlooked or denied, ‘The legacy of Terra Nullius sticks to our shoes with the dirt as we walk over Indigenous sovereignties every day … regardless of the individual and family migration trajectories that have brought us to this place’ writes critical whiteness scholar, Fiona Nicoll (2004).

[4] The Australian artist and scholar Ross Gibson refers to these forms as ‘memoryscopes’, see Ross Gibson’s Memoryscopes (2015), pp.vi.

[5] Lindsey, K. (2018). "Free way: the Hume Highway as a Spatial Narrative of Nation" in Australian Studies.

[6] Krause F.M. (1882) Geological sketch map of the Western Port and Cape Patterson coal fields. Originally prepared by F.M. Krause with additions and revisions by R.A.F. Murray under the direction of Thomas Couchman, Secretary for Mines and Water Supply for the Colony for Victoria, the Hon. Robt. Burrowes Minister for Mines. See: https://nla.gov.au:443/tarkine/nla.obj-231830637

[7] Stephen Muecke (2008) Joe in the Andamans and other fictocritical stories. Sydney: Local Consumption Publ.

[8] The term commonly used by newspapers offering accounts of the group’s alleged ‘outrages’ the time.

[9] Jan Roberts’ Jack of Cape Grim: A Victorian Adventure (1986), Clare Land’s Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner: The involvement of Aboriginal people from Tasmania in key events of early Melbourne (2014) and Leonie Stevens The phenomenal coolness of Tunnerminnerwait (2010) offer insightful accounts of the group’s ordeal.

[10] Not only does this place share the name as Gordon’s vivid poem but his descriptions of traversing wild coastal trails seem pertinent to the route we’re charting. That said, I also acknowledge the epic masculine qualities of his poem will not be everyone’s cup of tea. The frenzied urgency of the steeplechase it charts, the unashamed admiration for the reckless daring of the stockriders Alec and Jack, and the elegiac valour of the blood-hued filly who ultimately serves as the poem’s tragic hero, are probably quite off-putting to some.

[11] "FROM THE WRECK" (1927, September 17). The Mail (Adelaide, SA: 1912 - 1954), p. 15. Retrieved June 12, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article58531742

[12] Gordon’s From the Wreck passage reads: “Make sure of the crossing place; strike the old track / They’ve fenced off the new one; look out for the holes/ On the wombat hills.”

[13] Evelyn Araluen (2021), ‘The Ghost Gum Sequence’ in Drop Bear, p.4

[14] Short-finned glass eels arrive mainly during mid-winter to late spring, while long-finned glass eels come from mid-summer to late autumn. Short-finned eels spread along the entire Victoria coastline, while long-finned eels are only found east of Wilsons Promontory. Some will only loiter briefly in the estuary and migrate upstream while others will remain for some time. For more information about the short-finned eel see: https://vfa.vic.gov.au/education/fish-species/short-finned-eel

[15] The Water Story — A conversation between Jefa Greenaway and Samantha Comte, see https://art-museum.unimelb.edu.au/resources/articles/the-water-story-a-conversation-between-jefa-greenaway-and-samantha-comte/

[16] Ricky Prior interview with Joe Chambers. Wonthaggi & District Historical Society, Oral History Recording OH-0051, recorded 18th June 1982. Ricky started school in 1914 so the events he describes would have been before then.

[17] Joe & Lynn Chambers Out To The Wreck (1987), p.1.