Reminiscing on the family weekender

A tin shed, located on the verge of a property known as Wreck Beach Farm which has benefited from 30-odd years of rewilding, served as our family’s weekender for much of my life. Comfortable and self-contained, it became a gallery of curios and hand-me-down knickknacks: a battered but elegant fold-down wooden desk, my mother’s fathers, at which he typed an account of his WWII service and imprisonment as a POW in Europe;[1] blackwood chairs that once stood in the kitchen of my great aunt; cutlery from a dozen different homes that have served thousands of meals across hundreds of tables; and Indigenous paintings – Bush Tomato Dreaming, Butterfly Dreaming, The Seven Sisters, to name but a few – vestiges of my parents’ time working in remote communities in Australia’s north. Hints and marks of the past are obvious outside too.

Rutted trails worn by countless journeys made on the family tractor – a temperamental 1962 Ford that my father used to coax to life each morning – meander away from the shed to form an interlacing network that has been encrypted into the ground through iteration and time. Those trails pass battered hardwood posts, wildlife trails, rusting star pickets, and rotting tangles of sheepwire. Tiny monuments to the toil, triumphs, and misjudgements of those who have passed before. Wreck Beach Farm was purchased by my father’s parents in the early 1950s. My parents took it over nearly in the 1990s but their decision to sell in 2017 meant that responsibility for its custodianship has now been passed on to others. Before it sold, I tried to notice the details, enjoy the minutiae and eccentricities of a property I had come to know so well and one to which I had an inter-generational connection.

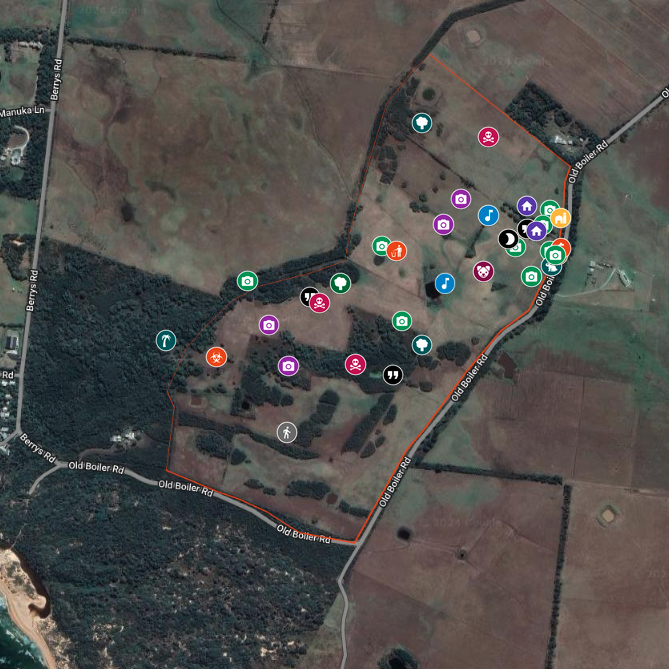

This interactive historical map 'Reminiscing on the family weekender' offers a snapshot of the intricacies, complexities, reassurances, and discomforts that accompany my affinity for my family's property 'Wreck Beach Farm' and its surrounds. It tries to understand and articulate the loss I felt when the property was sold and also comprehend the nostalgia I still hold for that place.

[1] A battered three-page facsimile of a typed account subsequently amended by hand can be found in the top drawer. Exactly (but only) 1,200 words accounting for 2,027 days spent in the Armed Services of which he spent two and a half years incarcerated as a Prisoner of War. Upon reflection, obvious connections can be made between Bob’s desire to document his past and my interest in recording those things that might go lost and unnoticed.