Track changes: Acknowledgement of Country

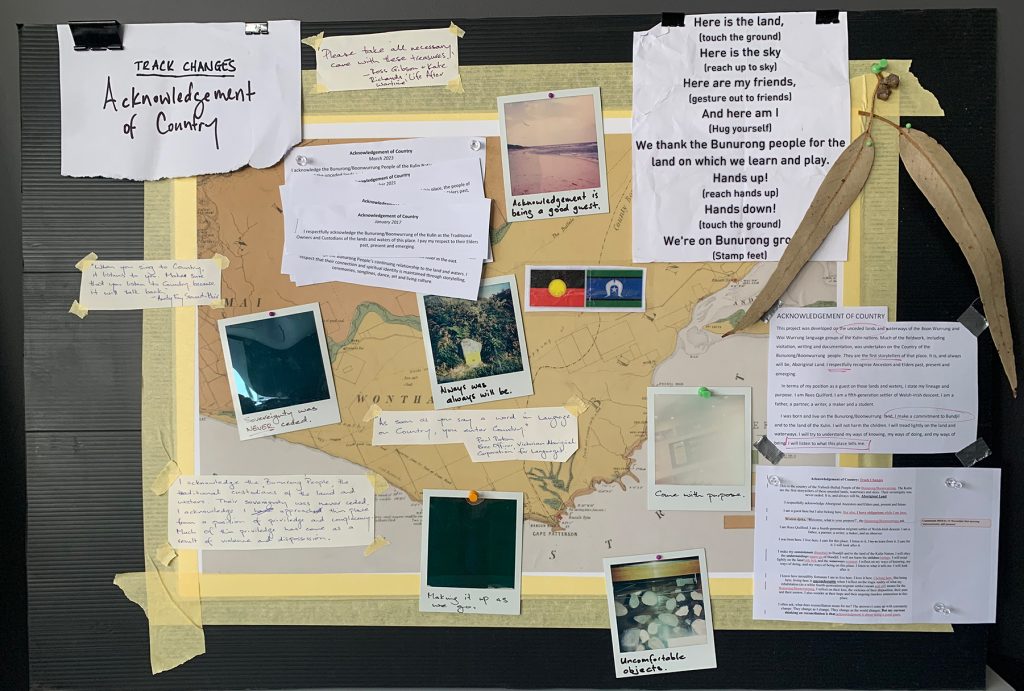

[Image: Layered mixed media amalgam exploring Track Changes and the iterative ever-evolving nature of my Acknowledgement of Country]

[Audio: Rees Quilford 'Acknowledgement of Country', January 2017.]

[Audio: Rees Quilford 'Acknowledgement of Country', March 2018.]

[Audio: Rees Quilford 'Acknowledgement of Country', December 2021, version 1.]

[Audio: Rees Quilford 'Acknowledgement of Country', December 2021, version 2.]

[Audio: Rees Quilford 'Acknowledgement of Country', March 2023.]

Background

Formal Acknowledgement of Country is a crucial cultural protocol in contemporary Australia. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have survived a long and horrific history of exclusion and systemic violence. This history of dispossession and colonisation lies at the heart of the disparity between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and other Australians today. At the same time, the resilience of Aboriginal Australia in maintaining and sharing vibrant cultural practices must also be acknowledged. My awareness of these counter-balanced realities has been rammed home throughout this PhD process.

The Bunurong Coast is stolen land, but acknowledgement protocols offer a personal albeit small opportunity to show respect for Traditional Ownership and acknowledge the continuing connection to Country. Offering an Acknowledgement of Country is one way I can formally recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It is a tangible contribution we can all make to ending the exclusion that has been so damaging (Australia, 2023). However, I am also acutely aware that the appropriateness of their usage and deployment varies widely. It spans from respectful to near-meaningless lip service through outright inappropriate.

Cases of the latter are terribly damaging and hurtful. As Wiradjuri writer and poet Jeanine Leane aptly puts it, those acknowledgements are “settler platitudes that do nothing to change ongoing dispossession and continued settler benefit on stolen lands” (Jeanine Leane, 2021 'Staring Back’). Sophie Cunningham also calls for careful re-consideration of the meaning of welcome:

“We need to think about the Welcome to Country that Australia’s invaders, my ancestors, neither sought nor, on the occasions it was offered, understood. About how that set us up to become the kind of country we are. A nation that’s been riffing on denial and forced handshakes since Captain Cook landed in 1770.”

Sophie Cunningham (2020) 'If You Choose to Stay, We May Not Be Able to Save You.' in Meanjin.

Given these sentiments, it is worthwhile contemplating the paradox of visiting and inhabiting Indigenous lands as a non-Indigenous Australian. Particularly the unresolved political questions of ‘them’ and ‘us’ and at what level are we the same people within one nation (Stephen Muecke, 2008: 86)?

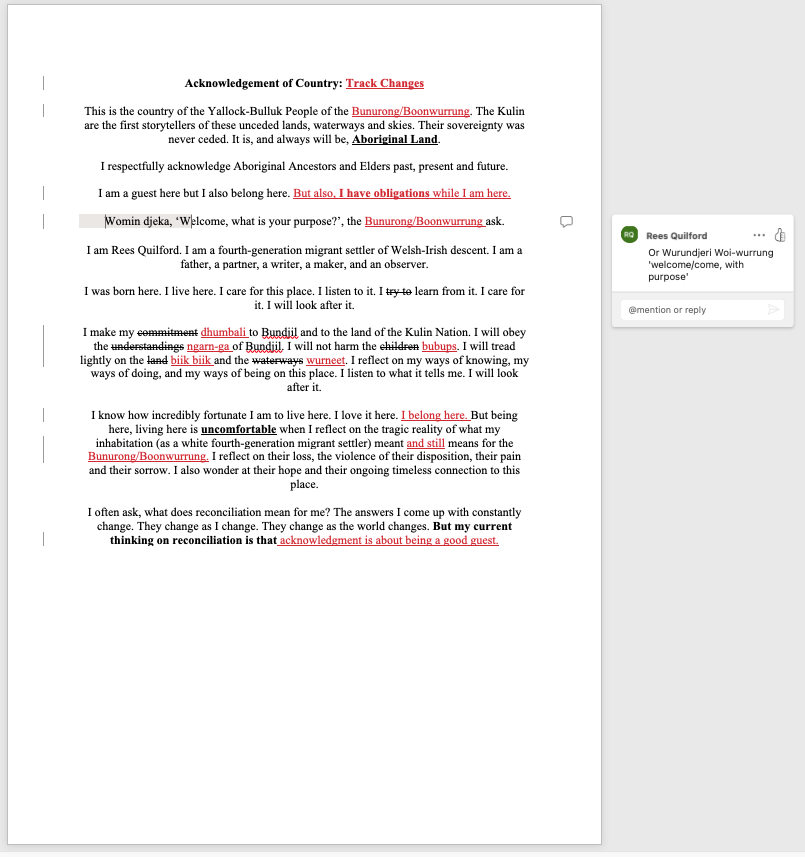

With all of this in mind, I find myself continually questioning and revising how I Acknowledge Country and my role as a visitor to it. There are so many complexities and personal nuances involved. For example, in the Woi Wurrung language, ‘wominjenka’ indicates a welcome. It is a phrase that adorns the organisational foyers and literature throughout the region I live in – businesses, local councils, schools, and government organisations all use it.

This Acknowledgement of Aboriginal custodianship is absolutely warranted, but it sometimes feels lacking in contextualisation to the point of being cursory. Due to this, for the longest time I failed to appreciate the broader meaning encompassed in that welcome. I have come to know that an appropriately accurate translation of wominjenka would be ‘Welcome, come with purpose’ or ‘What is your purpose, what is your business?’ (Bonnie Cassidy, 2020: 7). This is an important distinction from just 'welcome' at implies obligations and awareness on the part of the visitor. It implies informed visitation.

In my experience, when that welcome is formally offered by Bunurong/Boonwurrung community members and Elders it is generously given. However, it is a invitation that comes with obligations. Their generous offer allows me to visit and conduct business on Country, but in return, I should come with purpose, and, importantly, I need to be a ‘good guest’. I need to agree to heed Bunjil’s law[1]. This research project has helped me better understand these obligations.

Reflecting on Welcome and Acknowledgement obligations always highlights to me the profound truth and a bone-deep ancestral shame for the dispossession of Australia’s first peoples. But at the same time, I do not feel guilt, for as Tim Winton points out:

None of us are responsible for the culture and social conditions we’re born into. But that doesn’t mean we’re absolved from reflecting upon our inheritance.

Tim Winton (2015), Island Home: A Landscape Memoir, pp.225-6

When reflecting on my inheritance and privilege in relation to my recognising the Bunurong/Boonwurrung people and custodianship I always try to remember the strength, endurance and resilience people in maintaining vibrant cultural practices and connections to Country. In this way, the ‘Acknowledgement of Country’ I use is one small gesture in highlighting and celebrating connections that are being maintained, refined and shared so generously.

[1] Bunjil’s law insists no harm be done to the children, the land, or the waterways.