Wonthaggi’s Wartime Experience

of WWI volunteers (seen marching behind) in 1914. Wonthaggi and District Historical Society Photograph Collection.

“I would say to the House... I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat” was Winston Churchill’s submission to the House of Commons in his first speech as Prime Minister.[1] This bitter truth reflected the lived experience of the Second World War for soldiers and citizens alike. It also highlights the terrible toll extracted by all wars and armed conflicts. It is a burden known all too well by the residents of Wonthaggi and the surrounding area.

The citizens of the Wonthaggi district have played an essential role in Australia’s wartime history. Hundreds of men and women have served with great distinction. Tragically, many have made the ultimate sacrifice in service to their country. But enormous contributions have also been made, and tragedies have been borne by families, workers, and citizens away from the frontline. This essay highlights a small sample of Wonthaggi’s eclectic wartime experiences.

Conflict on the Colonial Frontier

Wonthaggi and the surrounding towns were founded on stolen Aboriginal land, that of the Bunurong/Boonwurrung people. The story of the Traditional Owners of this place since that European invasion is one typified by violence, dispossession, and deliberate silences. But it is also a story of fierce cultural resilience and active resistance. Contact with the notorious ‘Straitsmen’, unsanctioned sealers and escaped convicts[2] occurred from the early 1800s and brought violence, disease, and wanton abduction of Aboriginal women[3]. The situation only worsened with the arrival of settlers, graziers and land-grabbers[4]. The frontier war ultimately decimated the Bunurong/Boonwurrung, but they were by no means passive in the face of the violence and dispossession that occurred. The journals of George Angus Robinson, William Thomas and many other early settler accounts cite endless instances of active resistance, ferocious defence, and revenge raids undertaken by the Bunurong/Boonwurrung, by the various Kulin tribes, and by other Aboriginal visitors to this place.

The most well-known instance of this resistance is the 1841 confrontation between an Aboriginal group, labelled by the colonial press as the ‘Van Diemen’s Blacks’, and a European whaling party, which left two of the whalers, William Cook and Yankee, shot dead. The Aboriginal group – which included Parperloihener clansman Tunnerminnerwait, Planobeena (a Tasmanian Aboriginal woman from Port Dalrymple), Maulboyheenner (a bungunna or leader from the north-eastern Tasmanian region known to his people as Nalebunner), Truganini (a Tasmanian Aboriginal woman of Bruny Island) and Pyterruner (a Tasmanian Aboriginal woman) –spent the following weeks and months between fight and flight, raiding homesteads across the Westernport district while evading parties of mounted Border Police and squatter posses. Their ultimate capture led to the first executions in the colony of Victoria, the hanging in January 1842 of Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner.[5]

World War I

At the outbreak of the First World War, Wonthaggi was still very much in its early stages. Even though the town had only been established five years in 1914, the State Coal Mine was up and running. About 6,000 people lived in the town and its surrounds. Approximately 1,000 men were working underground. Thousands of tons of coal had already been mined.[6]

This made the mine and the town a critical strategic national asset in support of the wartime effort. As such, much of the town’s workforce—the miners, railway employees, and auxiliary staff—were deemed to hold essential roles. But that essential status didn’t stop many of Wonthaggi’s men from enlisting. Throughout the war, many left the mine and travelled to Melbourne to enlist; most gave ‘labourer’ as their occupation.

News that Britain had declared war on Germany reached Wonthaggi by cable on the night of August 4, 1914, or in the early hours of August 5. Wonthaggi’s councillors, mine staff and its residents took immediate action. By August 6, Wonthaggi’s Rifle Club members had been allocated to guard the State Coal Mine around the clock.[7]

More than 1,500 residents attended a public meeting on the McBride Ave. hill. At the meeting, Cr. Wishart proposed that “Wonthaggi form a citizen’s defence league for the purpose of doing our share in the defence of the State, Australia, and if need calls, the Empire.”[8] The motion was carried unanimously.

A local Patriotic Fund was also established to raise money to support the war effort. Under the heading ‘Troops for Europe’, the local paper also announced that Lieutenant Maxfield of the 48th Infantry (the local militia unit) would take enrolments from volunteers for the war in Europe.[9]

On the Tuesday afternoon of August 18, 1914, the Wonthaggi railway station was overflowing with people there to farewell the town’s first group of volunteers. Boys and girls were given the day off school, and many businesses closed to mark the occasion.[10] It was nearly nine months (in March 1915) before the troops' first letters began returning to the town.[11] Those letters, and many others, were published by the local papers.

News of the ANZAC landing at Gallipoli was reported in Wonthaggi’s Sentinel on May 7, 1915. The following week, the paper reported, “By their heroism and self-sacrifice they have won congratulations on their magnificent and brilliant achievements against a remorseless and implacable foe.”[12]

The community was not yet aware, but Wonthaggi had already lost two residents – Robert Johan Oliver and Harold Vernon Jordon. At least another eight would pay the ultimate sacrifice in the Gallipoli Campaign.[13] The Wonthaggi War Memorial commentates the names of twenty-six men who lost their lives in WWI.

News of heavy causalities at Gallipoli and on the Western Front began to appear in subsequent news reports. The ‘Roll of Honour’ section became a regular feature:

PRIVATE C.W. GRAY, wounded, is a son of Mr. W. (“Billy”) Gray, well-known member of the Powlett branch of the Australasian Coal Miners Association. He is 23 years of age and was employed in various capacities at the State coal mine almost from its commencement. He was one of the first of the Wonthaggi boys to volunteer and is a member of the 6th Battalion.[14]

It would have made tragic reading for local families and friends of those serving abroad. Those reports lasted three long years until November 1918.

The exact number of men who enlisted from Wonthaggi, or were from Wonthaggi and enlisted elsewhere, is impossible to tell[15], but the local papers reported it as more than 800.[16]

When news of the armistice with Germany finally arrived, Wonthaggi’s citizens celebrated for days. “[A]ll the town closed up, and splendid demonstrations took place during the afternoon and night”, the Powlett Express reported.[17]

World War II

The strategic importance of Wonthaggi and its mine was again obvious, perhaps even more so, during the Second World War. So much so that early-1942 Prime Minister John Curtin publicly praised the contributions. “The miners of Wonthaggi have voluntarily and without cost to the government built a splendid system of air raid shelters to meet the town’s requirements”, Mr Curtin stated in a public address.[18]

While geographically a long way from the action, Wonthaggi was deemed a prime target for attack. This importance was due to an acute demand for coal to operate the railway system and power the nation's munitions factories. “Every ounce of coal is wanted for our war efforts. Australia wants coal as much as she does guns, planes, and munitions”, claimed The Powlett Express in February 1943. [19]

Before the war, Victoria’s railway and industry supplemented supply with imported coal, most of which arrived by sea. This arrangement was a byproduct of the country’s various State railway networks using different gauge tracks, which made overland interstate freight both difficult and expensive. During the war, Japanese submarine activity along the eastern seaboard disrupted maritime shipping supply lines, meaning Victorian industry, including its munitions factories, relied heavily on local coal.

Wonthaggi’s miners heeded the call, and the Union pledged, on behalf of its miners, that the workforce would be fully mobilised. That meant the miners would refrain from strike action. Shifts were increased from two to three each day. The miners also worked Sundays and during their holidays.

In a 1942 public address, the Wonthaggi Union Official Mr J. McVicars highlighted the town’s miners' important work: “We can’t let our men down. We will not let them down. We intend to discipline ourselves, to see that no irresponsible action on our part leaves one ton of coal below that should be speeding on its way to some war factory.”[20]

Throughout the Second World War, coal mines across Australia operated at full capacity. That effort resulted in a greater output of coal than ever before.

Many of Wonthaggi’s residents also mobilised. This included individuals, local clubs and businesses raising a significant amount of money to support the war effort. It also meant adhering to strict blackout and food rationing requirements. Notably, that meant beer rationing across the state, much to the concern of local reporters, publicans and (most vocally) imbibers![21]

Many of Wonthaggi’s residents also mobilised. This included individuals, local clubs and businesses raising a significant amount of money to support the war effort. It also meant adhering to strict blackout and food rationing requirements. Notably, that meant beer rationing across the state, much to the concern of local reporters, publicans and (most vocally) imbibers![21]

Humour aside, inconvenience and fear permeated many aspects of daily life. Elaborate measures for civilian evacuation were discussed and planned. This included proposals to use disused mine tunnels as shelters in the event of invasion.[22]

Wonthaggi residents volunteered to monitor the skies for enemy activity. Sam Gatto’s book Wonthaggi Volunteer Air Observers Corps 1942-1945 details the exploits of the 32nd Wonthaggi Air Observers Corps. They commenced operations in January 1942. Volunteers observed the skies day and night for enemy planes, ready to alert the town of enemy invasion. Their vigilance continued for four long years. Up to 200 air spotters were involved, 70 per cent of whom were women.[23]

Wonthaggi’s recent wartime experiences

Wonthaggi’s various local newspapers also mention many servicemen and women from the Wonthaggi area who have been involved in Australia’s other armed conflicts over the years. This includes accounts from Korea, Vietnam, the East Timor peacekeeping efforts, and the Afghanistan and Gulf War conflicts.

For example, an edition of the Wonthaggi Sentinel from April 1952 includes a letter from Able Seaman Thomson of North Wonthaggi, who served in Korea aboard the HMAS Bataan. Thomson writes of bitterly cold temperatures and the action he saw with ‘The Reds’ against enemy gun positions positioned ashore. He also shares a humorous anecdote about how the ship’s captain lost his best suit. According to Thomson, “[the captain] swore revenge and from our past activities he is getting it.” [24]

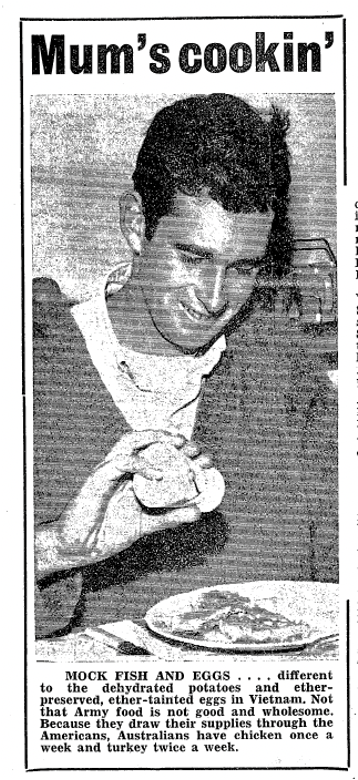

The local papers also include many pieces on Wonthaggi’s experience of the Vietnam War. There are reports of conscription call-ups, departures, visits home, the men’s experiences while in-country and their returns. Daryl Kerslake, Rob Dent, Jim and John Dowson, Bruce McKinnon, Graham Otte, John Quilford, Stan Whitford and many others are regularly mentioned.

The local papers also include many pieces on Wonthaggi’s experience of the Vietnam War. There are reports of conscription call-ups, departures, visits home, the men’s experiences while in-country and their returns. Daryl Kerslake, Rob Dent, Jim and John Dowson, Bruce McKinnon, Graham Otte, John Quilford, Stan Whitford and many others are regularly mentioned.

The August 28, 1967 edition of the Wonthaggi Express includes a report headlined ‘Our first boy is back from Vietnam’. It describes the return of Russell Morgan of Reed Crescent.

The interview describes Russell’s time in Vietnam, the foods he ate, his interactions with the Vietnamese, and action with the Viet Cong. Russell talks about his impending return to work as a storeman at Cyclone Forgings and his wedding plans. His parents are interviewed and speak of their relief at having him home safely.[25]

Jim Dowson talks of the importance of ANZAC Day commemorations in the documentary The Tunnel Rats, which the W&DHS has a copy of. It recounts the regular ANZAC Day reunions of the men he served with in the 3rd Troop, 1st Squadron, South Vietnam. In it, Jim says:

“Why are we so close? You know, forget the war, why are we so close? Really, I can’t put a why it happened. But there’s blokes out there, they’re like brothers. And I always try to think, know why is it? We were there, we had a job to do. We came back. Now we’re great mates.”[26]

Jim’s comments provide a fleeting glimpse of the camaraderie shared by those who have served but also hint at the broader sacrifice and toll of war. This essay highlights only a tiny sample of the diverse contributions and eclectic experiences of Wonthaggi’s servicemen and women, as well as the town’s residents during wartime. However, in doing so, hopefully, it conveys the importance of acknowledging the contributions and sacrifices that have been made by so many—both at home and abroad—during Australia’s armed conflicts.

This essay is an extended version of a speech delivered by Rees Quilford for Wonthaggi’s 2023 ANZAC Day commemorations. It draws heavily on the W&DHS local newspaper collection as well as Sam Gatto’s books ‘Contribution and Conflict: A History of Wonthaggi and the First World War’ and ‘Wonthaggi Volunteer Air Observers Corps 1942-1945’.

Notes and references

[1] Winston Churchill, First Speech as Prime Minister to House of Commons, May 13, 1940.

[2] Lieutenant John Murray reported the presence of sealers in Western Port during his 1801 exploration of the Australian south coast abroad the Lady Nelson (see Chambers, 1987, p. 7). Contact with sealers and escaped convicts and the settlers who followed had horrific consequences for the Bunurong/Boonwurrung people.

[3] Abduction, enslavement and the exchange of Aboriginal women was common amongst the so-called “Straitsmen” – sealers and escaped convicts inhabiting the islands of Bass Strait – in the early 18th century. There are terrible accounts of the treatment of Aboriginal women by these men but there are also stories of harmonious unions and family arrangements (Morris, 1988).

[4] William Thomas, the government-assigned Assistant Protector to Aborigines, notes in his journal that the settlement of Melbourne in 1835 served to “decimate the Bunurong people” (Stephens, 2014). Early settler accounts estimate the Bunurong/Boonwurrung as numbering between 250 and 300 people in 1835 (Thomas, M.L. and Jamieson, R. cited in Gaughwin & Sullivan, 1984, p. 88), a figure which Gaughwin & Sullivan (1984, p. 88) suggest was already much reduced from pre-contact numbers. Just a generation later (in 1864) Thomas reported just 11 Bunurong/Boonwurrung people living at the Mordialloc Reserve (Stephens, 2014). By 1877 The Illustrated Australian News (1877, p. 74) effectively declared the Bunurong/Boonwurrung extinct with the passing of Jimmy Dunbar. Fortunately, it was a pronouncement that proved to be incorrect with Bunurong/Boonwurrung culture surviving through ancestral lineage to five women who were abducted by sealers in the early 18th century (Council, 2009, 2017). The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council (2017) cites just five known apical ancestors – Elizabeth Maynard, Eliza Nowan, Jane Foster, Marjorie Munro and Louisa Briggs.

[5] Jan Roberts’ Jack of Cape Grim: A Victorian Adventure (1986), Clare Land’s Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner: The involvement of Aboriginal people from Tasmania in key events of early Melbourne (2014) and Leonie Stevens The phenomenal coolness of Tunnerminnerwait (2010) offer insightful accounts of the group’s ordeal.

[6] Sam Gatto, Contribution and Conflict, pp.8-12.

[7] Sam Gatto, Contribution and Conflict, pp.27-28.

[8] Powlett Express, August 14, 1914.

[9] Sam Gatto, Contribution and Conflict, p.30.

[10] Sam Gatto, Contribution and Conflict, p.31.

[11] Sam Gatto, Contribution and Conflict, p.35.

[12] Powlett Express, May 7, 1915.

[13] Sam Gatto, Contribution and Conflict, p.37.

[14] The Powlett Express and Victorian State Coalfields Advertiser, May 21, 1915

[15] Sam Gatto, Contribution and Conflict.

[16] The Powlett Express and Victorian State Coalfields Advertiser, May 16, 1916.

[17] The Powlett Express and Victorian State Coalfields Advertiser, November 15, 1918.

[18] The Powlett Express and Victorian State Coalfields Advertiser, March 6, 1942.

[19] The Powlett Express and Victorian State Coalfields Advertiser, February 20, 1943.

[20] The Powlett Express and Victorian State Coalfields Advertiser, March 6, 1942.

[21] The Powlett Express and Victorian State Coalfields Advertiser, April 2, 1942.

[22] The Powlett Express and Victorian State Coalfields Advertiser, June 28, 1940

[23] Sam Gatto, Wonthaggi Volunteer Air Observers Corps 1942-1945.

[24] Powlett Express, April 18, 1952.

[25] Wonthaggi Express, August 28, 1967.

[26] Jim Dowson in The Tunnel Rats which is held in the W&DHS Oral History collection (OH-0224).