Anticipation and anxiety

Scorching hot today, 41 degrees here in Wonthaggi. Must be roasting in the city. The museum – in the old railway station building – is surprisingly cool. Perhaps it’s the asbestos.

This local historical society is like many other rustic, self-managed collections in the post-colonial world: a ramshackle and messy archive of papers, knickknacks, and curios.

It’s also a testament to local and civic pride. Approaching it cynically, collections like these can seem a petty demonstration of parochialism. But there are plenty of other more sympathetic ways to look at this place — it is also a testament to past lives, triumphs, achievements, transgressions, and failures. It is a proud and personal form of remembrance. A way to pay tribute to those who have passed before. A celebration of small local things, the seemingly mundane and ordinary. It is a reminder of why the place I live is as it is.

Black-and-white staged photographs of stern gentlemen in three-piece suits commemorate achievements of apparent importance, the ‘1934 Members of Council for the Wonthaggi Technical School’ and the committee of the ‘Wonthaggi Leek Club’, which was founded in 1927.

Glass cabinets overflow with kitschy bottles, tins, and boxes—Bonox Jarred Cheese, Zeb Stove Polish, Liberty Sand Soap, Yellow Bird Stretch Nylon Panty Hose, and more.

Grainy, blurry and browning photographs document settler endeavour – bushies who’ve chopped down century-old trees, hat-wearing men pondering yarded cattle, pipes clamped firmly between their teeth. War memorabilia – tin hats, tin water cans, medals, journals and service medals.

Wonthaggi was a state-funded project—a mine and a town—so there is a mountain of photographs, documents, news clippings, maps, and objects related to coal, bureaucracy, and railways.

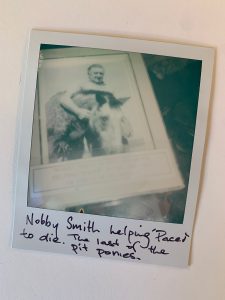

Then there are notable oddities and curios – things to pique the interest and tug at the heartstrings. An elegant black-and-white piano accordion patched with sticky tape and the leather underside cracked and worn through use. A beautiful photograph of a weathered old man and a bowed pony, both with world-weary eyes, ‘NOBBY SMITH, STABLE-MANAGER, HELPING “PACER” TO DIE, THE LAST OF THE S.C.M “PIT PONIES”[1]’.

A watercolour painting by my grandmother, Nell Quilford, captures an unnamed back lane. It celebrates 1970s suburbia in all of its ordinariness—red dirt track, outhouse dunnies, unkempt back fences.

A sparsely coloured wedding day portrait of a beaming bride standing next to a rotund and awkwardly seated groom. The painting, signed by Mourhouse, has a battered wooden frame decorated with elaborate metal trimmings and beige plastic paint. ‘FOB00122: Isaac “Ike” Hefford & Edna Sturgess’ is hand-written in biro on the back of the frame.

A gruesome iron polio frame once owned by the McFarlane family. They farmed an allotment in the nearby hills at Archies Creek. The frame was used to immobilise both their sons – Jack and Bill – who contracted polio as young boys in the 1930s.

Metal drawers full of the most beautiful maps, technical drawings, and geographical surveys. Family albums, folders containing sheets of hand-written minutes taken from committee meetings, booklets and ledgers – all yet to be catalogued are piled in every corner.

I sit amid this calamity, experiencing equal measures of anticipation and anxiety. What gems could I stumble upon? Where to start? How to make sense of any of it?

[1] The photograph was taken shortly before Nobby Smith euthanised Pacer.