Following Wonthaggi’s ‘Very Big Fish’

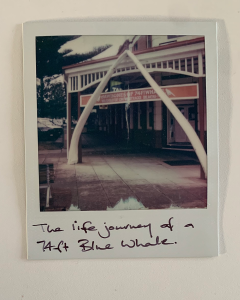

In 1923, a 74-foot Pygmy Blue Whale washed up dead on the Wreck Beach shoreline. A tangible reminder of the life journey of Wonthggi's Whale can still be felt in the jawbones that adorn the facade of the Wonthaggi Hotel.

Persistent echoes of that leviathan abound in local news reports, oral testimonies, and the memories of those who lived in the town when the ‘very big fish’ washed ashore.

On July 6, 1923, the Powlett Express reported “the magnitude of the monster”:

74 feet 6 inches long (22.3 metres), the tail was 13 feet (3.9 metres) wide, circumference 35 feet (10.5 metres) and the mouth was 17 feet (5.1 metres) in diameter, “large enough to take a bullock”.

Jack Keighly, an unemployed butcher, and Harold Pleydell, an unemployed miner, earned about £450 from chopping up and selling parts of the while, including blubber for oil.

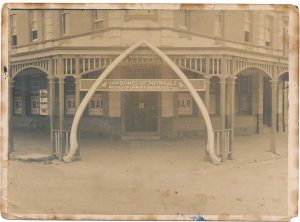

The jawbones of the whale were bought by Charlie Taberner, the proprietor of the hotel. They lay in the backyard for a few years, and were bleached by sunlight before being put into position at the entrance. After that they were regularly whitewashed to preserve them.

Joe and Lynn Chamber's wonderful monograph Out To The Wreck recounts numerous recollections of local residents making the long trek out to see the 'monster'. Those walking trips included formal school excursions, strolls made by family groups, and salvage missions.

[Audio: Fay Quilford reads an except from Out To The Wreck which recounts memories of walking out to Wreck Beach to see the washed up whale.]

It was quite the enterprise, pop-up lunch stalls were established to sell food to the visiting punters. Photographs were taken, and guided tours held. Apparently, the stench of the rotting carcass could be smelt nearly all the way into town.

Wonthaggi local Mark Robinson relates how his grandfather, Tom Ridley, went out to the beach to help cut up the whale and brought home the vertebra as a souvenir. For years it served as a pot plant stand on the Ridleys’ veranda in Broome Crescent.

When the house was sold, the vertebra came to Mark’s mother, Barbara, who was Tom’s stepdaughter. Mark remembers it being used as a chopping block until eventually his parents donated it to the museum, “I’ve known it all my life,” he says.