Carparks and frivolous placemaking?

Trailing the dog, I jog into the beach side carpark in the early autumn dusk. The place is typical of Bass Coast’s remote beaches, a secluded patch of gravel cut into the scrubby dunes.

I know the place well. I grew up here. The boundary of my parent’s farm is at my back, just on the opposite side of the road I came in on. I moved away more than 20 years ago but have remained a regular visitor. That situation changed recently when I came back to spend some time at the farm and write. My project has me thinking about place, history, and the hybridisation of physical and digital space.

This place, Wreck Beach and its surrounds, is pretty lightly frequented so its digital footprint isn’t large. A perfect spot for thinking about placemaking in the penumbra.

Skulking to the edge of the carpark, I play on my phone, trying to work out whether the carpark or beach has been configured as a digital check-in location on Facebook or Google.

My fumbling is interrupted when a big yellow Labrador bounds into the carpark. He charges up to Nahla, followed closely by the calls of his owner. The two dogs acquaint themselves quickly, sniffing and circling, as they are wont to do. Pecking order established, they set about mapping the carpark’s scents.

Max’s owner greets me, commenting on the beauty of the evening. I agree readily and make mention of the striking light I encountered along the road while running from my parent’s farm.

“Yeah, where’s that then?” he asks. We exchange pleasantries in that country way, cross-referencing acquaintances, mapping shared connections.

The man I converse with is Greg Brown – someone I’d known as a kid but haven’t seen in twenty years. We continue talking, he mentions the rising price of land and how this place, and this beach in particular, is getting busier.

There’s no doubting it’s a beautiful stretch of coast, this part of the Bunurong Marine Park. At high tide, the coarse golden sand merges with tussocked dunes and limestone cliffs. Low tide reveals a plush ecosystem of intertidal rock pools. A bracken-stained creek flows into the ocean just down from the carpark. The creek mouth is an important breeding ground for Hooded Plover, which are often seen scurrying back and forth along the beach.

Middens full of bleached shellfish attest to the feasts of this place’s first custodians, the Bunurong of the Kulin. They ate their fill of shellfish, abalone, limpets, crayfish, eels, and an abundance of bush tucker that can be found along the creek beds.

Post-European settlement, the beach has continued to be a place of play. Joe & Lynn Chambers’ local history monograph Out to the Wreck (1987) describes long summer afternoons in the 1920s spent amongst mobs of kids swimming, rock-pooling and fishing.

More recently, rapid population growth in the nearby coastal towns of Inverloch, Cape Paterson, Kilcunda and the accessibility of their beaches has seen Wreck Beach lose popularity. But the proximity to my parents’ farm meant plenty of time spent here. I remember walking undisturbed dunes and wading waist-deep through the creek to get to the beach.

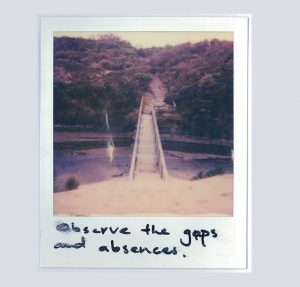

A foot bridge, built by the local council, now provides easy access to the beach. It has been well done, weathered wooden boards, span one dune to the other, fording a brown creek with green banks. It is the bridge that Greg complains about today, “It’s heaps busier here since the council built it for the bird watchers and their plovers. It’s the worst thing they did. Too busy now.”

We talk a little longer – discussing what his kids are up to and how my parents are adjusting to retired life – before exchanging farewells. He and Max slowly make their way across the carpark out onto Old Boiler Road. Turning right, they head toward their driveway, which is only a short way down the road.

Nahla and I stand alone as the last of the sun’s rays play on the leaves of the trees. Looking around, I wonder what Greg would make of this project. It’s hard to imagine he’d approve of anything that would bring more visitors to this beach. Even if those people did get a little more information about the history of the place. That thought only adds to my questions about the value of this exploration, a frivolous exercise perhaps, into digital storytelling and placemaking.

Then I remember none of this reflection matters, I love this place, as does Nahla. I hope it loves us too. That's all that really matters.