Echoes of Jim Mc

This story about Jim McDonnell – a man who would be remembered as the last hut dweller of this coastline – could be set at many different points in his lifetime. It could be framed around the teenage Jim, a skinny cocksure kid learning the ropes underground as an apprentice on the Wonthaggi mine. We could meet Jim as a young bloke who, driven by Depression necessity, has moved into a hut on the clifftop. That Jim whiles away his days fishing and combing the shoreline for driftwood and salvage. His nights are spent trapping and shooting. We could join a midldle-aged Jim who works as a Railway Ganger by day but still prefers the contented solitude as a coast dweller. Or we could dive headlong into wartime desperation, fear, and the weary slog of the muddy slopes of Pupa New Guinea. Another angle might be Jim on his post-stroke deathbed at the Wonthaggi Hospital. There we’d find him incapable of speech, longing to spend his suddenly imminent terminal moments overlooking the wild and rugged Bass Strait seas.

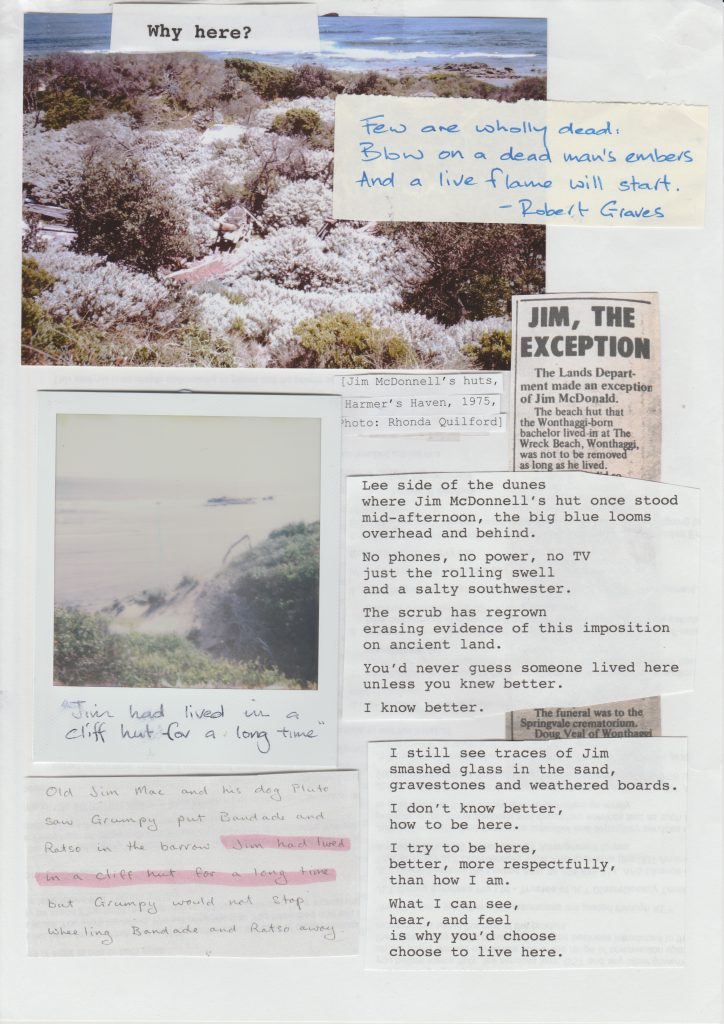

Jim spent most of the sixty-five years he graced this earth in those scrubby dunes. So, in a nod to the potency of his connection to that place, this story has been framed around the unruly clifftop dunes, how it was while Jim lived there, how it is now, and how it shaped Jim into the man we remember him to be.

Like so many who have lived, loved and thrived while on the shores, dunes and swampy plains of the Bass Strait coastline, James Henry MacDonnell is not a man often cited in history’s annals. His story is one of so many overlooked voices from this place. Not deliberately silenced in the same way as the stories and culture of the traditional custodians of this country, the Bunurong / Boonwurrung[1], but overlooked nevertheless[2]. This kind of rumination on the different lenses of history is not something Jim would have taken any interest in, except perhaps until the final stages of his life. But it is one of the reasons why I recount his story[3].

I never met or interacted with Jim. He passed before I was born. And nobody can know the experience and particularities of any life without having lived it ourselves. To tell a decent yarn, one must read between the lines and swap yarns with those who knew him. That said, the bibliographical particulars can help set the scene. Jim Henry McDonnell was born on the 15th of August 1910 in Outrim and passed away at Wonthaggi Hospital in 1976. The family home was located on Hunter Street in Wonthaggi, where Jim lived for much of his childhood alongside his siblings, including sister May and brothers Tom, Wally, and Ivan[4]. Jim went on to work as a coal miner and a railway worker. He served in the Second World War but it was that he was a man who opted for a different kind of existence, living alone on a section of coastline that he came to know as well as anyone could, that is of most interest.

We join Jim in the late Spring of 1959. It’s late afternoon. He’s working as a Ganger on the Wonthaggi to Woolamai railway line. He’s knocked off from the day shift and is riding a battered fixed-wheel bicycle home to his hut.[5] He’s compact, short even, wiry and supremely fit despite being on the threshold of fifty.[6] His complexion is dark and weathered from decades spent outside. This is a man who will spend most of the impending summer shirtless, getting about in just shorts and boots or sandshoes – walking, fishing, watching, beachcombing, tending his veggie patch. It’s a bloke who’ll likely appear on the cliff line or next to you on the beach as if out of thin air. My mother Fay, recounts being highly unsettled by his abrupt appearance on atop the cliff line.

Jim winds his way along the rutted sandy track with practised ease, making his way through the undulating Bracken flats and paddocks. His route roughly follows what is now a tarred road from Wonthaggi to Cape Paterson but for now, he traverses a series of interconnected dirt tracks. He’s about a mile and a half out of town, past Pommie Town, and is heading due south towards the coast. If he kept on the main track, he’d reach Cape Paterson in a couple of miles but instead banks right onto the adjunct trail at Cardamona’s Corner. He continues due south towards what then was a small collection of recently cleared farm allotments.

Jim’s mind wanders to the events of the day just past. Just hours earlier, Macdougal the striking Kiwi bay gelding won the Melbourne Cup at Flemington by three lengths. Ridden by Pat Glennon, he carried a weight of 8 stone 11 (123 pounds) and paid 8/1 in the old money. Irrespective of which particular nag won, the running of the Cup had again proved to be a lucrative exercise for Jim. He was not a gambler himself but was certainly an invested onlooker as he’d fronted a bob or two to most of the linesmen whom he worked alongside.

Money lending was a regular and lucrative side hustle for Jim. Both the Mine and the Railway pay weekly, on a Friday, and it’s fair to say that pubs and clubs in the town and across the district do a very healthy weekend trade. So much so that many of Jim’s co-workers find themselves a little short come Monday. The standard ‘lend’ is a quid (or 20 shillings). Enough to tide them over, enough to cover the family shop, bills and rent. They pay him back a Guinea (21 shillings) the following Friday. A small margin, but a margin nonetheless, one Jim justifies as an educational necessity. Discussing it years later with my father, “I don’t do it [the lending] for nothing,” he said “otherwise they’ll never learn. They’re bloody stupid, just one week off the piss and they’d be ahead.” The annual running of the Cup – the race that stops the Nation – has seen a boost in this stupidity and as such, much increased demand for his lending services. Jim does some rough calculations in his head as he continues on his way home. A rare few will be celebrating a windfall with the Macdougal result but there’ll be plenty in a bit of strife this evening.

It’s November, so the days are getting long and there’s still plenty of light. Jim’s weekday commute is approximately five miles, that’s the distance from the centre of the township of Wonthaggi out to the isolated coastal clifftop dwelling he calls home. Jim’s huts occupy a section of swale between the boundary of the farm recently purchased by my grandparents Arthur and Nell, and the wild unrelenting swells of Bass Strait.

He has occupied that beautifully secluded spot for decades, since around the time of the Depression. His time living on this coastline dates back longer than that but his first arrangement didn’t end well. There’s a hilarious anecdote about the misfortune that befell Jim’s first dwelling. Evidently, he’d established a tidy beachside fishing weekender about half a mile to the west, on the bank of Coal Creek at Wreck Beach[7]. Jim would likely have been Apprenticed at the State Coal Mine then.[8] Somehow, Jim had acquired possession of a box of water-damaged gelignite. This fortuitous happenstance was by no means uncommon for unused or overlooked mine equipment. Indeed, most of the shacks and huts that lined this coastline were built from materials salvaged or appropriated from the Mine. Naively, Jim left the gelignite to dry on the stovetop while he went fishing. Fortunately, no one was harmed when the hut was blown to smithereens and Jim was forced to start afresh.[9]

Apparently[10] the Townsend family had established and built a weekender fishing hut on the verge of what became the Quilford farm in the early 1930s and that is where Jim relocated his digs. At 21 years of age, Jim found himself unemployed after being laid off from the mine. Throughout the Depression of the 1930s, it was common practice for Mine Management to lay off single young men when they came of age to avoid paying adult wages. Continuing to live with your parents meant you didn’t qualify for the susso[11] so a flood of young men moved out of the town into what had previously been informal weekender fishing shack settlements. They took up permanent digs in the huts to take advantage of a bountiful coastline. They lived largely cost-free off the land and sea – fishing, craying, trapping and establishing elaborate gardens – while still receiving (albeit meagre) susso payments.

If we skip forward to today, those inclined to go looking for where Jim spent most of his life should veer off the Cape Paterson Road onto the gravel of Wilsons Road. Make your way south to the F-Break carpark. Follow the walking track through the marshy dunes, past the sandy rise that the surfers use as an informal lookout and change room, then down onto the beach. From there walk a kilometre or so westward towards Wreck Beach. Halfway along one of those arching sandy bays, an elaborate series of tracks wound their way up over the dunes to Jim’s ramshackle collection of huts. For those not inclined to go schlepping along the beach, instantaneous (but far less visceral and rewarding) access to the mise en scene of this tale can be obtained by simply logging on to Google Maps and taking a look at 38°40'00.3"S 145°35'17.8"E.

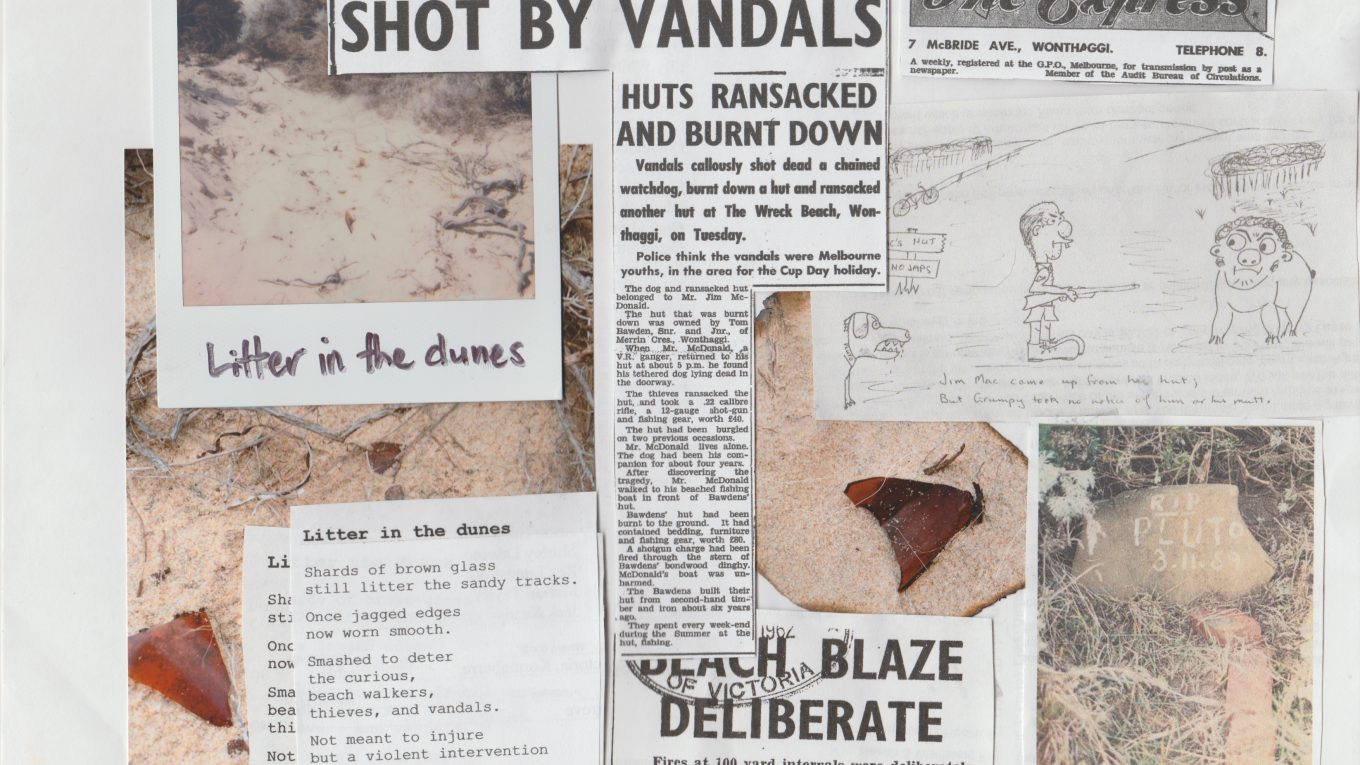

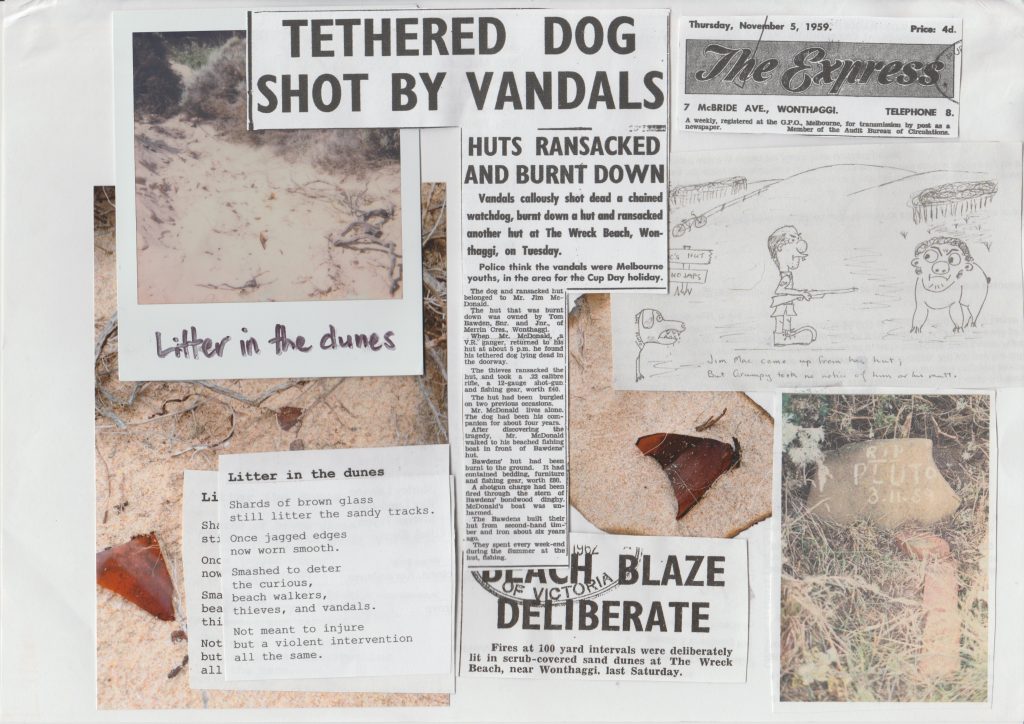

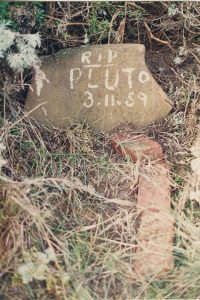

Let us return to the Spring of 1959 and Jim’s return home. It is, I’m afraid, not a happy day in Jim’s life. Jim crests the hill near his hut around 5pm. There, he leaves his bicycle leaning against a fencepost.[12] That rise looks out over a pristine soak to a stunning vista of the coastline stretching westward toward Cape Woolami and eastward in the direction of Wilson’s Promontory. The weather is mild, and the wind calm but the ocean has a foreboding roughness to it. Jim pauses to note a thin trail of black smoke rising skyward from some unknown source about a mile down the beach near Coal Creek. Shrugging, he walks the couple of hundred yards across the paddock towards the cliff line and the snug collection of ramshackle huts and salvage that lay below. It’s a stunningly beautiful spot, sheltered from the bitter so’westerlies a northern aspect for the winter sun while a thick blanket of Banksia, Sheoak and Coastal Wattle provide shade and respite from the summer heat. The eerie silence tells Jim something isn’t right. A feeling of dread and fear begins to rise from the depths of his guts. Passing through the prolific vegetable garden he maintains at the top of the hill; Jim crests the clifftop and sees the senseless act immediately. Jim’s knees buckle but he manages to propel himself forward. Jim runs to Pluto, his faithful companion of about four years[13], who lays dead in the doorway. Shot where he’d been left tethered.[14] The dog is cold and lifeless, its lifeforce ended in the blink of an eye by a single calculated rifle shot through its brain. Collapsing beside his companion, Jim lays his head on its cold bloodied fur and begins to weep.

This isn’t the first time Jim’s hut has been ransacked, in fact, it’s the third time in the past couple of years. The previous robberies rattled him, but the callous shooting of his only permanent companion is different, this is cold-blooded murder. Jim hasn’t felt this kind of dread since the bloody and muddy slopes of PNG. Jim enlisted at age thirty[15], joined up just three months after his half-brother Wally was killed in action.[16] Joining the South Gippsland Regiment, the AIF’s 22nd battalion, he served from 1941 to 1946. One thousand five hundred and forty-seven days of active service which included six months in PNG. A stint during which he saw action against the Japanese. The South Gippslanders were celebrated for the guts and determination they showed during a gruelling forced pursuit of the retreating Japanese. Jim and his mates took back a herculean 50km of those hilly muddy tracks in ten days of action. The Kalgoorlie Miner described it as the greatest march of the New Guinea campaign[17], reading that report made Jim proud. But seeing Pluto here dead in the dirt brought back the soul crushing existential dread and terror that had dominated his very being throughout the war.

The war wasn’t kind to Jim or the McDonnell family. Jim’s brother Wally, a Stoker-Engineer in the Royal Australian Navy, was killed in duty in March 1941, when the H.M.A.S Perth was sunk off the coast of Java. Smashing his elbow while under fire and a nasty bout of Malaria saw Jim spend lengthy periods with the medicos. His bent elbow forced him to shoot off the opposite shoulder, not that big an inconvenience compared to the lingering effects of the malaria, even the mildest of cough knocks him about. All that pales in comparison to the tragedy that happened back here. Jim had a girl when he left for the war. They were engaged to be married and had planned to when the war ended. But she was killed in a car accident while Jim was away. Perhaps the pain of losing his fiancé is why he hasn’t been comfortable in the company of women since.[18] Perhaps it was that trauma, love tragically lost coupled with the weariness of five years on the Front. Perhaps it was something else but when Jim was discharged back in 1946, he didn’t return to life in the town, instead, he opted for the quiet solitude of these dunes.

That peaceful solitude seems a lifetime away right now. It takes Jim a long time to regain his composure. The shadows are getting long by the time he stands. Jim slowly bends down and unclips Pluto’s collar before scooping the dead Spaniel up in his arms. He carries him a couple of yards away from the mouth of the hut and lays him gently down beneath a Sheoak.

He will bury his companion in the grey sandy soil of the clifftop soon enough but now there’s business to be attended to. It will be dark soon and Jim still has to inspect the wreckage wrought by the thieves. A quick survey of the ransacked hut reveals they’ve done a good job of it: Jim’s .22 rifle and 12-gauge shotgun are nowhere to be seen as his best fishing gear. About £40 worth gone by Jim’s reckoning.

Jim shakes his head wryly, so much for a Cup Day profit. Pulling on his cap, Jim makes his way up over the dunes, past a series of beehives and chook pens, then down onto the beach. His fishing boat is beached in front of Bawdens’ hut, about half a mile westward.[19] Jim looks to the sky but the story it tells doesn’t bode well. Jim’s boots trace heavy through the soft yellow sand as he trudges toward the pall of black smoke that rises skyward ahead of him. Where the Bawdens’ hut once stood Jim finds a smouldering heap of second-hand timber and twisted corrugated iron. What remains still burns blue because of the sea salt. Jim’s boat is unharmed but the Bawdens’ bondwood dingy is ruined, its stern blown out with a charge from Jim’s stolen shotgun. With a despondent shrug of his shoulders, Jim turns and begins retracing those heavy footfalls back to his hut. The Express will report the vandalization on the front page. The police blame the callous destruction on visiting Melbourne youths. The locals know different. Jim doesn’t think about any of this, instead he has to bury his dog.

Later that night, Jim sits in his hut with nothing but a kerosene lamp[20] and the dull roar of breakers meeting the shoreline for company. Enclosed as he is by salvage, a hut of galvanised iron, planks, flattened kero tins and hessian taken from the beach, the mine and town. Jim has finished his tea, premium cut steak[21], and the gnarled Teatree roots, driftwood and beach coal[22] in the IXL oven are smouldering low.

At the end of war, Jim had taken a job on the Victorian Railways. Started as a Ganger, then worked his way up to Head Ganger. He’d worked the same line for nearly fifteen years by the time we meet him, and it was a vocation that Jim would continue for another decade until retirement in his early sixties. But that was only a tiny part of his life, the larger more fulfilling element was the Jim’s life-long relationship with this place. It is a stunningly beautiful spot. A place one can while days and weeks away fossicking, camping, sitting, listening, and reflecting. It gets hot at the height of summer and wet and windy in the depths of winter, but Jim knew his way around that.

Not since the Boon Wurrung had lived off these lands had anyone been as attuned to the daily, weekly and seasonal rhythms of life in this place. It’s doubtful anyone has developed the same localised knowledge since. Long-time Cape Paterson resident Ronny Gilmore recounts that Jim had an encyclopaedic knowledge of local conditions. “He knew what rock to stand on, on what tide, at what time of year to catch a particular fish,” Ronny told me more than fifty years after Jim last graced this place. John Quilford recalls seeing Jim carting in boxes of Garfish with tails as thick as pick handles. He netted by night as well as setting lines for shark.

[Audio: John Quilford (interviewed by Rees Quilford) reflecting on seeing Jim McDonnell riding his bike into town with a box of garfish to sell. Recorded 11 July 2017.]

Jim knew that the snapper would run with the winter Tea Tree bloom. He knew every crayhole, each gutter and sandy channel. He knew how to read the rabbit runs, fox holes and wombat warrens. ‘Trapper’ was the profession Jim gave when enlisting[23] and that is an apt summation of his life. Jim was a man who lived apart, lived by the rise and fall of the tide, the wax and wane of the moon. Jim was a trapper, a fisherman and a beachcombing extraordinaire.

While it is true that Jim had chosen a different life – one that literally straddled the threshold of culture and nature – he did entertain a steady and regular stream of visitors. Family, friends and acquaintances often ventured out to Jim’s huts for overnight or weekend stays. Before his death, Jim’s father ‘Talky’ was a regular visitor to the hut. The old man would drive his horse and buggy out to the beach each weekend. Tinlegs Baker and Phil Dell would drive whatever paddock bomb they owned at the time (some with blown-out tyres stuffed full of Teatree) out to visit. They’d spend their time fishing and salvaging coal from the beach seams. A San Remo based fisherman was another regular visitor – he’d spend a week or so camping there each summer. He would harvest coastal Teatree then weave it with wire to make craypots. A young Tommy Gill spent two years living with Jim in the mid-1950s after falling out with his family, as an old man he described the experience as the best time of his life[24]. In the later stages of Jim’s occupancy, his sister May and her one-armed Mercedes driving husband built a hut at the same site and lived there for about six months prior to relocating to Cape Paterson. Jim had also mounted a battered old plank of wood atop the dune which provided a bench seat on which he would sit with a cup of tea and survey the ocean. There he would often be joined by beach walkers and passers-by for a chat and a cuppa.

[Audio: John Quilford (interviewed by Rees Quilford) reflecting on Jim McDonnell littering the tracks around his hut with broken glass and shell grit.]

Despite those visitors, the robberies and unwanted visitations obviously worried Jim. That anxiety will see Jim take to smashing empty beer bottles and collecting broken shells to cover the beach tracks in and around his huts.

The aim was to ward off unwelcome visits from beach-walkers or representatives from the Lands Department, whose officers continually threatened him with eviction in the latter stages of his life.[25]

Walk the beach today and can still see brown shards of Jim’s broken glass in the sand, their edges now rounded smooth with time.

[Audio: John Quilford (interviewed by Rees Quilford) reflecting on Jim McDonnell's interactions with the Lands Department. Recorded 11 July 2017.]

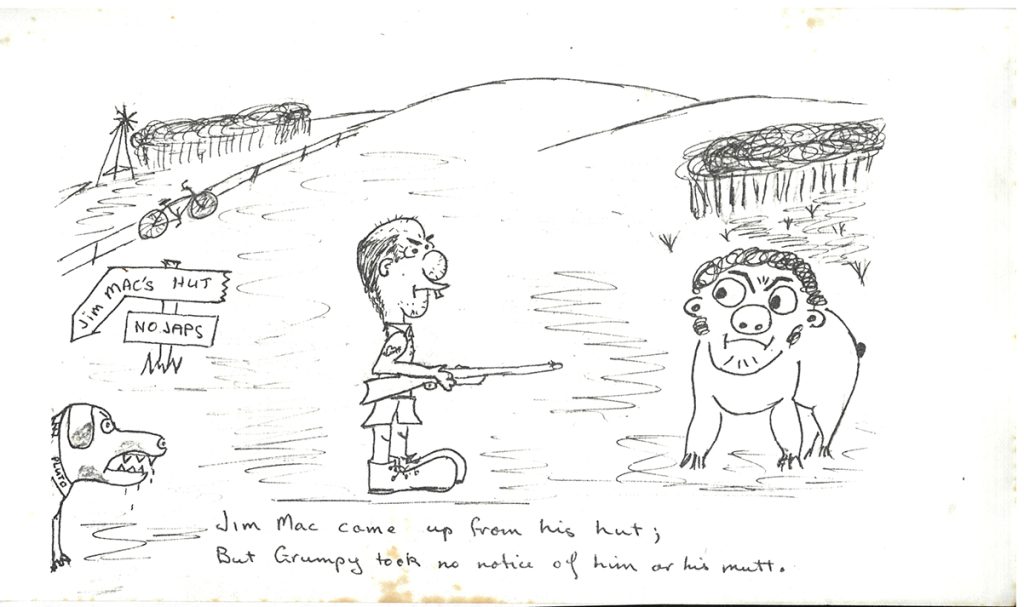

This didn’t have much effect. In 1962 a deliberately lit coastal fire will burn out 100 acres of coastal scrub at Wreck Beach. Jim’s huts were again threatened but survived. A couple of years later, Jim was confronted on the track by a group of three Italian men wielding a rifle. They were making to shoot and steal a pig from the Quilford’s stye. Jim stared them down, telling them that if 40,000 Japanese soldiers hadn’t managed to kill him, then what hope did ‘three city dogs’ have.

In 1968 a luxury yacht, the Winston Churchill, owned by the then Victorian Secretary ran aground on the rock platforms below Jim’s huts. The road was bulldozed to tow the boat off the rocks. It certainly improved the ease of Jim’s daily commute but also increased access to the beach.

Jim would live the final stages of his life under the threat of eviction. Staff from the Lands Department began to visit more regularly, poking around in search of the dwellings. Jim pulled down two of the huts on the site in order to make his occupancy less conspicuous. Jim McDonnell was allowed to remain, the last remaining hut dweller.

In July 1976, Jim suffered a major stroke. He was taken to Wonthaggi Hospital. He was to attend the wedding of John and Rhonda Quilford – who by then lived in the farmhouse just half a mile from Jim’s huts – just a couple of weeks later. He was unable to make it. The soon-to-be married couple visited him on the morning of their wedding. While he was still supremely fit, he passed away a couple of weeks later, aged 65. Staff from Land’s Department wasted little time. They demolished the hut and removed a lifetime of salvage within three weeks of Jim death. That signalled the end of the hut dwellers of this place.

Notes

[1] The Bunurong / Boonwurrung families inhabited this section of coastline for millennia, caring for and nurturing the lands, its waterways, and its skies. They are known to have maintained permanent camps through what we call summer and early autumn. The dunes adjacent to where Jim’s hut once stood are filled with middens that overflow with bleached shellfish and bone fragments from generation upon generation of king-tide feasts. That way of life was violently stolen and destroyed with the European invasion. The rupture and devastation of Aboriginal life and culture was so severe that these shores were largely unpopulated until the early twentieth century when makeshift fishing huts and weekends began to spring up. That Jim lived the majority of his life on the lands of the Bunurong / Boonwurrung but probably didn’t give the irrefutable reality of the unlawful violence they were subjected to much thought is testimony to the pervasive power of appropriating narratives. Their rich and valuable experience, culture and knowledges need preserving and telling but that is the remit of other work.

[2] Jim’s was the last of a long line of women, men and children who inhabited the scrubby dunes of what is now known as the Bass Coast coastline. As mentioned above, the Bunurong / Boonwurrung families inhabited this section of coastline for millennia upon millennia. The ‘Straitsmen’ and so-called ‘desperate types’ – escaped convicts, thieves and maritime bushrangers – arrived to these shores in the early 1800s to hunt seals, whales and Aboriginal women. They were followed by a smattering of free settlers who took up pastoral runs and mining allotments. From the early 1900s through to the 1960s this coastline was home to dozens of fishing huts and weekenders. The diverse and eclectic stories – moral or otherwise – of most of these people have largely been lost and overlooked by historical and literary narratives.

[3] The length of Jim’s lived in the dunes attracted significant local interest and notoriety. The intrigue and nostalgia of his non-conventional living arrangements meant knowledge and memories of his existence endures. The fifty-odd years he spent living on that cliff line was reason enough to warrant an entire chapter in the Joe and Lynn Chambers much loved local history monograph Out To The Wreck. Frank Coldabella also wrote a wonderful rumination on the details of Jim’s life for the Bass Coast Post. His life and the connection with my family is also why I was asked to deliver a talk for the Wonthaggi & District Historical Society museum more than forty years after his death.

[4] The names of Jim’s siblings have raised much contention amongst those I’ve talked to. The newspaper archives present conflicting accounts of the genealogy of the McDonnell family. But the

[5] Jim commuted into town daily by bicycle for work. Later in life, as the area opened up more and more, he might hop a lift in the back of trucks and cars of local farmers and friends. Junior Little and my uncle John Quilford, who both ran dairy herds on the adjacent farms, would often do kerosene drops for him. John recalls once seeing Jim humping a 100-pound gas cylinder to the hut on back of his bicycle.

[6] Jim’s military service records list him standing just 5 foot 3 inches, with blue eyes and a dark complexion.

[7] Joe & Lynn Chambers Out To The Wreck (1987, p. 27)

[8] Following in the footsteps of his father, Jim began his working life at the age of 15 and worked the Kirrak Shaft from 1925 to 1932. His miner’s tag number was #1865.

[9] Yet another instance of historical contestation, this entire story has been contested by some of those I have spoken to who indicate that Jim never recounted such an incident, it’s cracking tale, nevertheless.

[10] Interview with James Quilford, conducted 2019.

[11] Government welfare payments.

[12] Members of the Quilford family recount vivid memories of seeing Jim’s bike leaning against a fencepost beside the gravel track that traverses the family farm. He would leave it on that rise then walk across the paddock and over the cliff line down into the swale and his huts. The salty air and the wear of those coastal tracks and meant Jim wore out a bike every year.

[13] Jim was always accompanied by a dog, he kept spaniels, all of which were named Pluto. Three of them are buried in the Cape Paterson dunes.

[14] Tethered Dog Shot by Vandals’, The Express, 5 November 1959, p1.

[15] According to his service records, Jim enlisted with the A.I.F at Wonthaggi on 5 June 1941. His service records specify ‘Trapper’ as his profession at the time of his enlistment confirming that he would have been spending a lot of time out at the huts at that time in his life.

[16] Land Air Sea

[17] Kalgoorlie Miner

[18] This observation was made by my mother many decades later. She spent many years visiting the Quilford farm and swimming at the nearby beaches but despite seeing Jim on many occasions, she never formally met or spoke to him.

[19] Jim kept a fishing boat at Wreck Beach Bay. He left it tethered upside down in the dunes and would carry a 1.5 horse powered outboard down from the hut to fish.

[20] Jim’s night-time lighting was provided by kerosene lamps, although he had previously (unsuccessful) attempted to rig electric lights using a car generator. Jim also kept a kerosene fridge but also used a cave at the base of the cliff face for cold storage.

[21] While Jim was a prolific fisherman and trapper, he preferred premium steak sourced from the local butcher. The only fish Jim ate was Whiting.

[22] Which Jim regularly chipped out of one of the coal seams – dubbed King, Queen and Rock by William Hovell in 1846 – that snake their way through the rock platforms below Jim’s hut.

[23] Jim McDonnell service records.

[24] Frank Coldebella, ‘The coast dwellers’ Bass Coast Post

[25] In the 1930s the Victorian Lands Department began a process to evict and demolish the hut along this coast. By the 1950s the pressure was mounting on the hut owners along this stretch of coastline. As a result, the huts at Cape Paterson, Eagles Nest, Harmers Haven, the Oaks and Shack Bay slowly began to disappear.