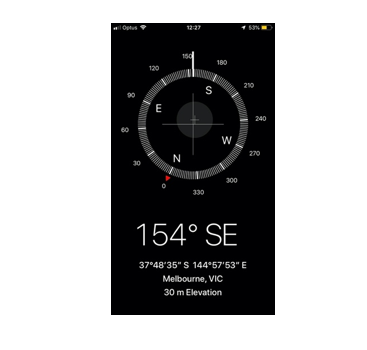

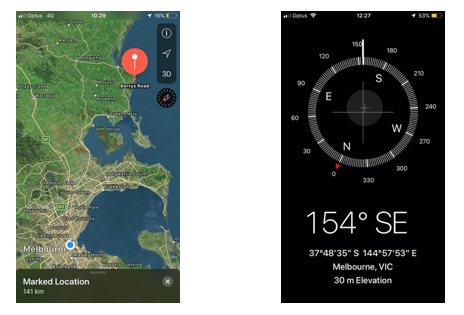

154 degrees southeast

It’s early in the day so I have my choice of seat. I hesitate as I must choose carefully – one’s orientation should mirror one’s endeavour. Slowly pacing the circular reading room, I assess every aspect. Finally, I reach my resolution, choose a desk. One angled 154 degrees southeast. One facing the backdrop for the content and landscape I interrogate.

It’s early in the new year, the beginning of a new decade, one commencing with the country ablaze. I will spend the day, and several days beyond, in the State Library of Victoria. Undertaking a forensic yet reflective exercise in sense-making, I will contemplate my connection to a particular place, one located many miles away. The library has recently undergone weighty renovation but despite the appeal of its shiny new spaces I have gravitated to the ornate domed reading room. Its appeal is writ large, etched into the wall:

TO SLIDE INTO THE DOMED READING ROOM AT TEN EACH MORNING, SPECIALLY IN SUMMER OFF THE HOT STREET OUTSIDE WAS A SENSATION AS DELICIOUS AS DROPPING INTO THE WATER OFF THE CONCRETE EDGE OF THE FITZROY BATHS

HELEN GARNER

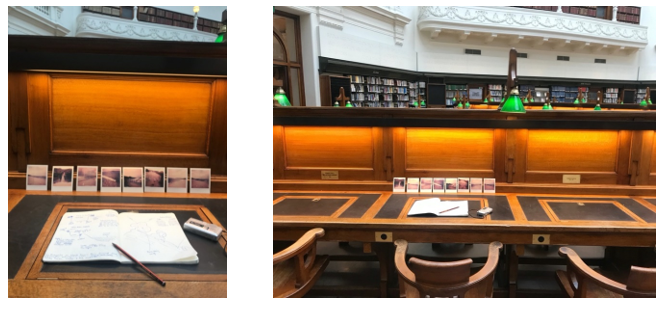

There, in the delicious cool, I will continue to review my documentation. The archive of concern is minimal: a handful of photographs, an audio recording, and a few handwritten notes. A subjective chronicle of a specific piece of coastline, its waterways, its grey sandy soil, and its imposing skies. A journal of time spent inhabiting the beautiful scrubby dunes and the undulating paddocks of what is currently known as the Yallock-Bulluk Marine and Coastal Park in Victoria’s southeast. He has known it as the Bunurong coast. Through an act of practiced revisitation, I hope to make some sense of the place of my birth and the backdrop for much of my daydreaming.

I select the only unnamed seat in the row. To the left, a commemorative plaque:

NICHOLAS, LACHLAN,

TOBY AND CHELSEA ARMSTRONG

1992

to the right:

MORRIS BARDAS

1905 – 1959

To be free of the implications associated with inhabiting a space memorialised to other individuals offers temporary relief. A rare instance when maintaining distance from the messy entanglements seems not to be a hinderance. Unpacking a cache of documents, I wonder about the strangers named on these tiny little plaques. I speculate on their hopes, their unrequited longings, and their temporal displacement.

My interrogation of stories from the past is more than a simple search for truth, it demonstrates an urge for survival beyond death. This urge, I recall somebody suggesting, is what lies at the heart of all archival projects: that something about each of us, whether profoundly intimate or even mundane, will leave an imprint that future generations will respond to and hopefully treasure (Johnson 95-6). Perhaps this same urge extends beyond archival projects and actually encompasses most, if not all, creative endeavours.

These imprints of the past can be located everywhere I look on the coastline of my concern – in paddocks, on beaches, and in the shedding bloom of banks of teatree. I have beheld them in battered hardwood posts, encrypted into wildlife trails and rusted onto star pickets. They are apparent in the rotting tangles of sheep wire that serve to arbitrarily delineate one property from another. They are imprints that can be located in the archives and the landscape itself. They can be found people’s memories and their reflections. They are engraved into the plaques similar to those fixed to the seats beside me.

These echoes of the past are manifest in a brace of Polaroid photographs, the single tape recording, and the small black notebook that I place on the reading desk. They offer glimpses and testimony of personal affinities, sympathies, attunements, confusion and parochialism. What’s ‘local’ in local history?’ asked a renowned historian (Dening 74) in one of the serious books about history I once read. There’s something eminently universal about local history according to that scholar. It concerns and is of the substance of our all of lives, they wrote. The meanings and connections that can be read into a specific place, its multifarious histories, and the records that chronicle those things, seem to echo the sentiments of that scholar.

An occasional grain of sand can be seen and felt on the images, vestiges of the arcing bay on which they were taken. Gently running a finger over the notebook’s cover, encrusted as it is with salt from the very same place, I can almost smell the sea on the afternoon breeze. I carefully prop the polaroids against the ornately carved timber panel and the green reading lamp on the partition illuminates their evidential qualities.

The domed ceiling rears above, offering a suitable reminder of the colonial project that it, and my inhabitation of that coastline, are the product of. A quote carved into the dome hording catches my attention:

The studious silence of the library…TRAQUIL BRIGHTNESS

JAMES JOYCE

Turning my focus to the documents at hand, I recommence a journey of forensic analysis. I will pour over these photographs, records, and collected notes for days. I will search, ponder, reflect, and interrogate.

It is a search that will encompass regular forays into the library’s varied collections. Acts which will contextualise and complicate. This soundboarding will raise questions about the process of examining records of a particular place while located in a distant and vastly different place. I will reflect on the different sensory experiences entailed in my analysis. I will ponder how my approach informs and shews the personal archive I work with. I will ask the same question of my inhabitation and interaction of the library’s iconic institutional archive. I will try to remain attuned to the gaps, the absences and the cultural disjunctures. Perhaps I will finally make some sense of what can be read from my personal record of a particular place, made at a specific moment. Perhaps I will make some sense of the place I am so inclined toward.

The chronicle I contemplate documents a stretch of scrubby dunes, arching bays and undulating bracken plains running from Inverloch to San Reno. It is a place – or an infinite collection of places – special to me. It was my childhood playground and a place which is also special to those close to me. For me, and them, that stretch of coastline is where meaning is made (Plumwood 139). A site of self-identification (Gibson 8). It is not an unchanging and fixed entity. Nor is it a static, closed or so-called ‘authentic’ location (Massey 6). Like many other places, people have and will continue to pin beliefs and perceptions to it. But for me, the the Bunurong coast is an intricate and ever-changing physical, metaphysical, and historical ecosystem. It is a complex entity overflowing with an abundance of organic life, movement, sounds and smells. It also brims with echoes, fragments and remnants of the past.

A nexus of significant historical happenings occurred there. Middens teeming with bleached shell fragments from generation upon generation of Bunurong king-tide feasts litter the dunes. My thoughts turn to the people that have inhabited those coastal lands and seas over millennia, of those who might tread its sands after I am long gone. The marine park on that strip of coast is named after its Indigenous custodians, the Yallock-Bulluk of the Bunurong. I reflect on their loss, the violence of their disposition, their pain and their sorrow. I also wonder at their hope and their ongoing timeless connection to the place. I wonder at generation upon generation who have swum in those waters. I think of all of the actors, living, past and inanimate, that call the place home.

Those Bunurong middens overlook a crescent bay – one with a system of big sandy dunes, and where a brackish creek meets the sea – which since European settlement has borne witness to three shipwrecks and a beached whale. A weathered bluestone cairn on the verge of the beach carpark once commemorated the explorer William Howell’s find of black coal in 1826. The plaque has since been jimmied and the cairn now memorialises other occurrences. Rude huts built in the early-1840s by the coal exploration team that surveyed those seams once stood beside the waterway – Coal Creek as it is currently known – near where it meets the ocean. Those huts and the nearby dunes were the site of an 1841 confrontation between a group of Tasmanian Aboriginals and a European whaling party which left two of the whalers shot dead. The Aboriginal group spent the following weeks and months between fight and flight, raiding homesteads across the Westernport district while evading mounted police and squatter posses. Their ultimate capture led to the first executions in the colony of Victoria, the hanging of Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner.

The barnacle-encrusted rusting iron girders that litter the rock platforms are remnants of the wreck of a three-masted 1,155-ton wooden barque, the Artisan, which ran aground there in the early hours of Tuesday 23 April 1901. Those girders – visible at low tide – are a tangible reminder of the past. Traces of the life journey of a 74-foot Pygmy Blue Whalethat washed up dead on those sands in 1923 can still be glimpsed and felt via the jawbones that now adorn the façade of a nearby hotel. Persistent echoes of that leviathan can be found in news reports, oral testimonies, and the memories of those who lived in the town when the ‘very big fish’ washed ashore.

It’s not just those grand historical narratives that have occurred in the place of my concern, but also the mundane and the ordinary – buildings, vessels and people have come and gone. Day trips have been enjoyed. Long meandering walks have been made. Packed lunches have been shared, hands have been held, tears shed, and kisses have been exchanged.

Then there are the various hut dwellers who have inhabited the dunes of that coastline. From the 1900s through to the 1970s, coal miners, fishermen and families built and used ramshackle weekenders. Collectives of young men saw out the Depression there. One man – Old Jim Mac – lived most of his life in the hut he built on the lee side of the dunes. A veteran of the Second World War, Linesman for the Victorian Railways, fisherman, trapper and squatter, Old Jim passed more than fifty years ago. He lived a life directed by the ebb and flow of the tide, by the direction of the wind, by hopping from one fishing hole to the next. Mentions and asides relating to his life can be found in the records – employment and service archives, newspaper clippings, birth and death certificates – but more important and moving traces of Jim can still be located in the landscape he inhabited for all those years. Shards of brown glass – their once jagged edges now worn smooth – that he smashed to ward off curious beach walkers still litter the dunes. The gravestone of his dog Pluto can still be viewed on the clifftop, as can the overgrown skip line he dug into its face. Traces and whispers of him also still exist in people’s memories. Recollections of him lugging boxes of fish and rabbits into town by bicycle. Stories of Jim walking the beaches at dawn searching for timber to salvage.

The act of thoroughly integrating the significance of these historical occurrences, both the grand and the everyday, involves navigating an intricate network of interrelations. It involves acts of speculative imagination and picking through those tantalising strands that extend back through time. It involves observing the landscape itself, examining the documentation, memories and testimonies of that place as well as sifting through the archival records. Like all places, the section of coast that I ponder is a product of associations, relations-between and co-dependencies. It is constantly being made and remade. It is never finished, never closed, it is a simultaneity of stories-so-far (Massey 9).

I try to remember that all acts of speculation entail an element of risk, where one has to traverse unknown territory. “One doesn’t arrive—in words or in art—by necessarily knowing where one is going”, someone much wiser than I once said or wrote, “you work from what you know and what you don’t know” (Hamilton 68), they added. In other circumstances this inclination towards ambiguity would likely frighten me. However, under this bastion of scholarly learning with its aged tomes and vaulted ceilings, the opaque process seems both appropriate and liberating. Embracing uncertainty seems to offer a productive avenue towards insight, humility and existential grounding. Reflecting on my visitation and documentation practices, I realise that embracing uncertainly has helped me wonder at the majesty and mystery of the coastline of my childhood. It helps me appreciate the privilege of listening and learning from place. It reminds me of the obligations that accompany my position as a guest on these lands. It provides clarity when I walk the lonely sands, swim the cold seas, and sit in the dunes so full of life and mystery.

Works Cited

Dening, Greg. ‘What’s local about local history’ in The Victorian Historical Journal, 52(207), 1982, 74-77.

Gibson, Ross. “Orientation: Remote, Intimate, Lovely” in P. Ashton, C. Gibson, & R. Gibson (eds.), By-roads and hidden treasures: Mapping cultural assets in regional Australia. Perth: UWA Publishing, 2015, 7-15.

Johnson, Miranda. ‘Indigeneity and the Archive: Mediating the Public, the Private and the Communal’ in P. Ashton, C. Gibson, & R. Gibson (eds.), By-roads and hidden treasures: Mapping cultural assets in regional Australia. Perth: UWA Publishing, 2015, 87-98.

Massey, Doreen. For Space. London: SAGE, 2005.

Plumwood, Val. ‘Shadow Places and the Politics of Dwelling’, Australian Humanities Review 44 (2008). Sourced at: http://www.australianhumanitiesreview.org/archive/Issue-March-2008/plumwood.html